Spirited Away: An Exploration of Japanese Identity

Reconciling Japanese Tradition and Western Modernity from the Meiji Era to Today

Spirited Away, awarded the Best Animated Feature Film Academy Award in 2003, is not just a coming-of-age story about a 10 year old girl. It is a film that explores the tension between Japanese tradition and Western modernity without drawing straight lines demarcating that “Japanese” or “tradition” is good, and “Western” or “modernity” is bad. Instead, it complicates these ideas to show that neither one is clear-cut, and suggests that whilst Japan must not forget its roots, these can be reconciled with Western modernity to form a new Japanese identity.

In the film, the world of the bathhouse represents a past Japan of the Meiji period during which ideas of Japanese traditions were challenged by Western influences. The bathhouse is a place of leisure for Shinto gods, “kami,” who arrive in huge ships that resemble the makiwarabune of a famous river festival in Japan, the Tsushima Tenno Matsuri. However, whilst these gods are respected and pampered, the reason why they are treated this way is because they are valuable customers of the bathhouse who are the source of Yubaba’s wealth. Yubaba herself, an overall antagonistic character, lives in a lavish Western-style penthouse, wears Victorian style clothing that contrasts to the more “traditional” uniforms of the workers, and is obsessed with money. Moreover, in the “modern” world where Chihiro comes from, Shinto religious symbols are completely disregarded—there is a strong sense that they have been forgotten and neglected by how Shinto statues covered in moss stand in overgrown forests, and Chihiro’s parents pay no attention to them as they journey into the tunnel to the other world. These factors combined suggest that Western influences have corrupted Japanese tradition, and have made Japanese people neglect and forget their roots.

However, Western influences are not always depicted negatively, and the film reconciles this tension between Japanese tradition and Western modernity. Yubaba’s sister Zeniba, the “good witch,” also lives in a Western style home. The difference is that Zeniba’s home is less grand and lavish, and is more humble and cozy. This shows that “Western” does not always equate greed and overconsumption. Moreover, this contrast between Yubaba and Zeniba is significant, as although they are identical in appearance and abilities, what they do with those abilities is what sets their characters apart. This emphasizes human agency, and the ability for humans to choose their path in life, suggesting that likewise, Japan has a choice in its own future. Modernization does not have to mean giving into excess and greediness, and Japan does have a choice to remember its roots, something that Miyazaki felt strongly about.

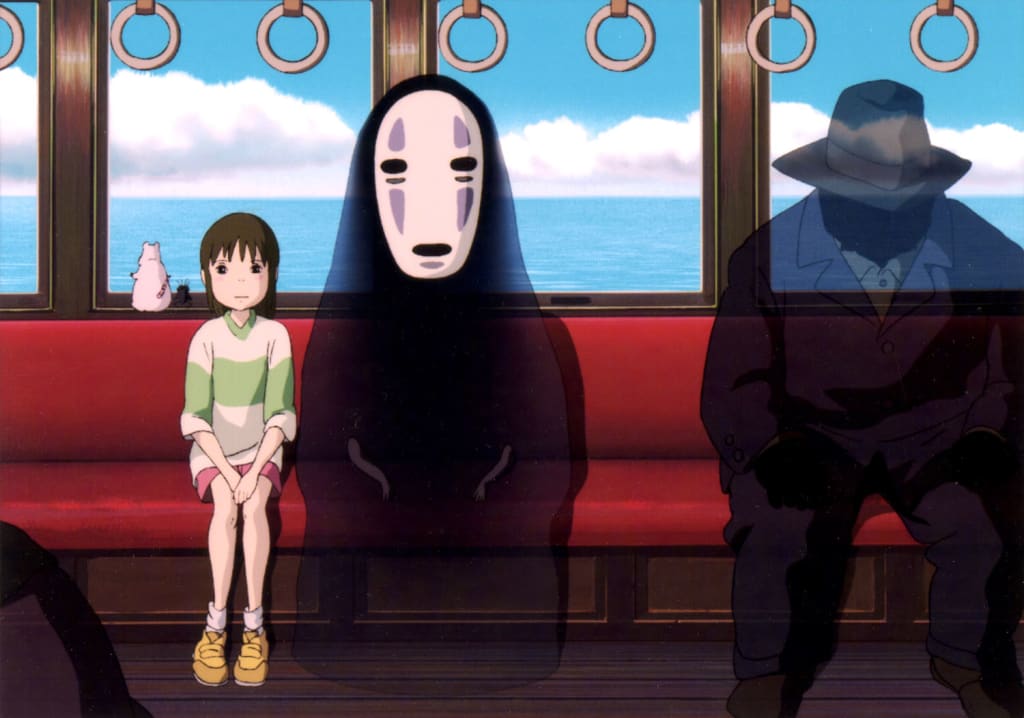

Furthermore, the train that Chihiro and No Face take to reach Zeniba’s house is also a way in which this tension is explored. Andrew Yang argues that in Spirited Away, the train is “blatantly out of place” as it does not fit into his vision of the film representing “two Japans,” one of “consumerism, state institutions, and technology,” and the other of “magic, rituals, and spiritual beliefs.” However, I disagree with this argument, as the film does not divide these two worlds so simply, and in fact, the train is an important symbol that represents this bridging and intertwining of Japan and the West, tradition and modernity. In the Meiji period, the train became a powerful symbol of Western modernisation, and in this bathhouse world that represents the Meiji era, the train is a key icon that indicates modernisation is taking place. Furthermore, the passengers on the train represent the forgotten parts of Japanese tradition that are literally being carted away by the train of modernity, an idea that is reflected in the passengers’ translucency and lack of identity. It is also significant that there is no return train, and that the passengers get off the train at stations that are surrounded by nothing but water, which is emphasized by the extreme long shots. These factors further emphasize this point that something important is being irrevocably lost.

However, although the train is an important symbol of modernisation that is carting away tradition, it is also a practical means of transportation that is the sole means of escape from the bathhouse. In the film, Rin says that she will one day also take the train and get away from the bathhouse, and of course, the train is the only way by which Chihiro can get to Zeniba’s house in order to save Haku’s life. Therefore, the train is not only a symbol of modernisation that is carting away tradition, but it is also an important means of progress and attainment in Rin’s case, and survival in Chihiro and Haku’s case. This shows, as Yang argues, “the ambiguous role of technology and manufactured items in Japan... neither wholly beneficial or detrimental.” In other words, Western modernization is not completely negative and can be beneficial if applied appropriately.

Furthermore, Spirited Away does give warnings about how Japan has been going about its modernisation, especially with regards to environmental destruction. This is manifested in two incidents in the film. The first is when the “Stink God” comes to the bathhouse. His monstrous body is brown filth that smells horrendous too, but once Chihiro removes the “thorn” from his body, he is purified and reveals his true identity as a River God. The “thorn” turns out to be a bicycle handle that is attached to an enormous pile of manmade rubbish including a toilet, a fridge, metal scraps and oil barrels. As Susan Napier argues, this shows how the river, “despoiled by modern civilization... has become a sacrifice to consumer capitalism.” This scene clearly shows the way in which humans and our economic activity has polluted the environment. The second incident that shows modernisation’s impact on the environment is when Haku remembers his true identity as a River God. On their way back to the bathhouse, Chihiro tells Haku about how when she was little, she fell into a river that no longer exists because it has been reclaimed to build an apartment building. This shows how humans have taken over the homes of Shinto kami and spirits, displacing and disrespecting them and nature.

However, both scenes can also be read as an optimistic view of how humans and modernization, and tradition and the environment, can coexist. In the first incident, the cleansed River God wears a noh mask, representing a traditional Japanese art form. Furthermore, the kami and staff of the bathhouse cheer at the successful removal of the rubbish by waving fans with the Japanese rising sun on them. This suggests that underneath the cultural pollution, traditional Japanese values still exist and can be renewed again. In the second incident, we see Chihiro and Haku holding hands and soaring through the skies above the clear water and the clouds. Haku is a River God, representing traditional Japan, whilst Chihiro is a human from the present-day Japan, representing modernity. This scene, therefore, can be read as a personification of these two worlds and how they can be reconciled. Furthermore, in both incidents, it is human Chihiro who “saves” these Gods and rectifies the consequences of human activity. This shows how humans have agency and gives an optimistic view of how Japan can amend the environmental destruction that they are causing, and that modernisation can coexist with traditional Japan.

Spirited Away does not define Japanese identity as an opposite to Western modernity, but shows how these ideas of Japanese, Western, tradition, and modernity, intertwine in complex ways. The film explores the tension between these values from the Meiji era to today, showing how Japan can reconcile these ideas in order to create a new Japanese identity. This new Japanese identity is one that can embrace modernity and influences from the West, whilst preserving its “traditional” values that can help to moderate the transformations of modernisation.

References

Goulding, Jay. "Crossroads of Experience: Miyazaki Hayao's global/local Nexus." Asian Cinema XVII, no. 2 (2006): 114-123.

Grunow, Tristan. “Constructing Modern Japan”. Lecture, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, October 13, 2017.

Napier, Susan Jolliffe. "Matter Out of Place: Carnival, Containment, and Cultural Recovery in Miyazaki's Spirited Away." The Journal of Japanese Studies 32, no. 2 (2006): 287-310.

Runnebaum, Acchim. “Tenno Matsuri”. Japan Daily. July 26, 2017. https://japandaily.jp/tenno-matsuri-4295/.

Suzuki, Ayumi. “A Nightmare of Capitalist Japan: Spirited Away.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 51, (2009).

“Tsushima Tenno Matsuri”. Kikuko's Nagoya resource website. Accessed December 10, 2017. http://kikuko-nagoya.com/html/tsushima-tennou-matsuri.html.

Yang, Andrew. “The Two Japans of 'Spirited Away'.” International Journal of Comic Art 12, no. 1 (2010): 435-452.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.