8 Mysterious Paintings that Break the Fourth Wall

These pieces of art know that they are pieces of art.

In European art and literature, everything has a structure. A story has grammar, syntax, plot, characters, and setting. Paintings have colors, shapes, textures, techniques, and symbols. Part of this logical schema of the arts, is the concept of art coexisting with real life. Does life inspire art, or vice versa, or both, or neither?

This is where the so-called fourth wall comes in. Even the etymology of the phrase is debated. Some people claim that it references the separation of the audience from the actors on stage, a metaphorical "fourth wall," in addition to the walls of a playhouse building. Others speculate that it goes even deeper than that, and that each "wall" represents a degree of separation. The first wall represents the character being aware of the other characters, the second represents the existence of fiction in their own universe, in the third wall the characters acknowledge that they are in a work of fiction, and the fourth is when the characters address the audience directly.

Whichever school of thought you might subscribe to, these are paintings that break the fourth wall, in one way or another. These artworks nod toward themselves, their creators, and their viewers alike. Here is a brief timeline of self-referential art, spanning 500 years from the 15th century to the 19th century.

1. 'The Arnolfini Wedding'–Jan Van Eyck, 1434

Created in 1434, this was a seminal painting for early Flemish art.

This painting is called The Arnolfini Wedding, or Arnolfini Marriage, Arnolfini Portrait, and many other similar names. Despite the title, it is unclear who this couple is, and whether or not they are even getting married! It is an educated guess at best, to assume that the subjects are the Italian merchant, Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini, and his bride. Much of this artwork is lost to obscurity, and therefore, open to speculation, and interpretation.

With our modern ideas of romance, we naturally assume that the holding of hands represents intimacy. But in the 15th century Netherlands, could this be a socio-political gesture? Modern audiences might also assume that the female character is pregnant, as suggested by her swollen skirts, and her hand placed tenderly over her abdomen, in an almost maternal protectiveness. While most people, myself included, think that she is obviously expecting, others posit that this is just the boxy style of medieval garments. If she married the merchant Arnolfini, then she could afford more fabric to display more wealth.

Consider the facial expressions on these two individuals. The woman has a blank stare, which personally, I find disturbing. But the man certainly looks sinister, and threatening, with his furrowed brow, stern countenance, and unsmiling lips. His hand is raised, as if hushing the woman, or commanding her to stop. He seems to be the figure of authority. Others posit that his hand is raised in greeting, as if waving at the viewer. But I disagree, given the rest of his body language, and the overall tone of the picture in general.

The mirror is literally and figuratively at the center of this unique artwork. It is strategically placed in the middle of the landscape, above the clasped hands of the mysterious couple, and below an extravagant brass chandelier. Even the spherical shape is symbolic of sacred geometry, and impossible perfection. In its silver surface, you can see the reflections of two figures. Are these the couple in the foreground? Or is it the painter, and the viewer, transposed into the painting, as if by magic? Or are they two strangers, whose mysteries are yet to be unraveled? Even the frame of the mirror is imaginative. It reminds me of the sun, or a flower, or even of an industrial gear shape.

You might have to squint to read the loopy cursive script on the wall, over the central mirror. Even then, it is difficult to make out the artist's signature, signed out mischievously, as if real graffiti on the wall. When you focus so close on this minute detail, you might start to notice other small secrets, hidden in the nooks and crannies.

That four poster bed, curtained with red velvet, sure looks fancy. So does that intricate Persian rug. And that cute, fluffy little dog in the foreground. But what's with those weird shoes in the lower left corner? Why is the male figure barefoot instead of just wearing those sandals? The window offers us a sliver of the outside world, but nothing more. This whole scene leaves me with more questions than answers.

2. 'The Ambassadors'–Hans Holbein The Younger, 1533

One of these things is not like the others...

The Tudor dynasty, during which King Henry VIII reigned, gave us this curious oil painting. Like many of his contemporaries, the German painter Hans Holbein would use symbolism in his work. For example, the two globes could represent travel and politics. The lute could symbolize music, and the arts. The books could be a visual metaphor for knowledge, and learning.

These were mostly familiar objects for the Tudor audience. But what is that warped oblong shape, beneath these everyday items? If you squint your eyes, or tilt your head, you might recognize it. Memento Mori. "Remember, You Will Die." In other words, a human skull.

The modern eye might think that this resembles a cheap photoshop. This looks like a stock image of a skull, stretched out with a simple computer program. But this was painted with oil pigments, in 16th century Europe. This is a sophisticated artistic technique known as Anamorphosis, or forced perspective. When viewed from a certain vantage point, the skull is proportional, and anatomically correct. Back in those days, this painting would be hung in the stairway. That way, people could see the skull staring back at them, as they descended down the stair steps.

Of all possible paintings, why did Holbein include this macabre little secret, in a realistic portrait of important political figures? Why did he juxtapose it with normal trinkets like spyglasses, and maps? Many art historians would say that it is to emphasize human mortality. Even the rich and famous have to die. Travelers, scholars, and even royalty will all face death. Just like everybody else.

3.' Las Meninas'–Diego Valesquez, 1656

Las Meninas is an intriguing piece from the Spanish Golden Age of art.

Diego Valesquez was a renowned painter in Spain during the 17th century, in the age between the Baroque and the Renaissance eras. His painting reflects the ambiguity and uncertainty of rapidly changing times. Las Meninas, meaning "The Ladies-In-Waiting," is a canvas full of tension, and unease.

Front and center is the young princess, Margaret Theresa. Long blonde hair flows around her chubby cheeks, and her small body is already decked in heavy silk gowns, and a constrictive farthingale of wood, steel or bone. The princess is just a little girl, but she is already burdened with the roles, and responsibility of royalty.

She is surrounded by odd characters; A dog, a chaperone, a bodyguard, two women with Achondroplasia, and two Maids of Honor. These are the titular Ladies in Waiting, or Las Meninas, that gave the painting its name.

If this isn't already convoluted enough, just wait til you notice the creepy old man in the background. The one wearing all black, and standing in the doorway. Who is he? Is he coming, or going? Is this an early example of the so-called "Vanishing point" in classical paintings, where the background resembles natural depth perception? This technique revolutionized realism, and three dimensional paintings, and it also gave the backdrop a focal point in its own right.

It gets weirder. There are paintings within the painting. See how seamlessly the oblong door slips into the geometric pattern. Notice all the rectangular frames in the background. Too bad they are too dark to see clearly... Except one.

Why does the "painting" in the center of the canvas look so clear, and bright? Why is it placed so prominently, near the cherubic face of Infanta Margarita, and also near the the dark-attired man in the back door? Is it even a painting at all? Many art historians speculate that it is actually a mirror. Therefore, it is reflecting the image of King Phillip IV, and Queen Mariana of Spain. This explains the two figures, one tall and masculine, the other more petite, but both commanding pomp and circumstance.

But wait... If the viewer is facing the "mirror" in the painting head on, and it reflects the royal family, does that mean that the audience was intended to be the King and Queen? Even if that was the case, how can you explain the painter himself making a cameo appearance? He occupies most of the lower left hand corner, but his dark hair, complexion, and clothes blend with the bleak paintings and drab walls in the background. Diego Velasquez painted a portrait, of himself painting a portrait.

What is he painting within a painting? Is it the profile of the royal couple, seated before him, reflected in the mirror? Is he painting the very same portrait that he himself is in? The more you think about it, the more self-referential it becomes.

4. 'Self Portrait'–Marie-Gabrielle Capet, 1783

Marie-Gabrielle Capet was one of the few female students at The Royal Academy of Art in 18th Century France.

In the 1700s, Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, or the Royal Academy of Art, admitted only four women at a time into their French campus. Marie-Gabrielle Capet was one of them. Her extravagant, detailed work was exemplary of Neoclassicism: A revival of Baroque, and Renaissance techniques, which in turn were inspired by the Greco-Roman greats.

These layers of detail bring depth to the painting. The illusion of texture on the satin, and lace. The subtle variation of light on human skin. The meticulously posed model: Herself.

This is the French 1780s equivalent of a fire Instagram selfie. It's almost an act of pure vanity. Observe her facial expression, the heavy lidded "come hither" look of a vixen. Cheeky make up, with a vivid rouge, making her face blush. Skin as pale as a porcelain doll. Hair bigger than an 80s glam metal band. Gorgeous dress of opulent blue fabric, probably silk or satin.

When I see her easel, and paintbrush in view of this painting, I think of mirror selfies where the phone is visible. It's like,"Yeah, I'm taking a picture of myself. So what? It's not my fault I look fine today. "

This also raises the question: Did she alter her own image in this painting, to be more flattering? This would be comparable to modern day filters, or even photoshop. The possibilities are only limited by the artist herself. Whether or not she embellished her own appearance, there is no denying that she was a talented painter, and a lover of beauty.

In many ways, this might be considered an ordinary self-portrait. But how intriguing! The canvas in the painting is blank, or faded with time. Not even pure white, it is a dark, splotchy gray. This drab canvas is a stark contrast to lovely lady who painted it... Or will paint it. Or is currently painting it? It is unclear whether the dreary canvas is a work in progress, or a piece not yet started, or the very same self-portrait that it is in.

5. 'Escaping Criticism'–Pere Borrel De Caso, 1874

Everyone is a critic, especially when it comes to classical art.

In Victorian era, the industrial revolution took hold, and our modern world was created in the process. Just like technology and society, art was also evolving. The techniques of classical art were at odds with the conceptual abstractions of modern art. Even back in those days, artists felt misunderstood, and they were especially antagonized by critics.

Classical painters would mock religious and political figures, but they took offense when they themselves were satirized. In the modern era, the creative types are still reputed to be sensitive artists. Hell, even I'm guilty of this. I write whatever I want about music and art, positive or negative, but I get discouraged when my own writing is challenged.

The relationship between art and reality is so blurred. Is it even possible to separate the artist from their art? What if even the artwork itself is desperate to just exist, free from judgements, and expectations? The only way for art to break free from criticism, is to break free from itself. Perhaps the only way to do this, is to no longer be art. As the oft-quoted saying goes: "Art should comfort the disturbed, and disturb the comfortable." This is symbolized, on multiple levels, as the subject of a painting flees from his own picture frame, eyes frenzied with emotion, limbs clambering out of the canvas, and into the real world.

6. 'Model Making Mischief'–Raimundo Madrazo Y Garreta, 1885

A Rococo model breaks her pose, to draw a cartoon of the artist himself, on her own portrait.

The art of Europe is known for extravagant detail, beautiful women, and creative symbolism. this is especially true of the Rococo era, which favored exaggerated femininity in ruffled lace, pastel colors, big hair, and sometimes even make up. This painting by Spanish artisan, Raimundo Madrazo Y Garreta, is a prime example of the Rococo art style, but with a whimsical twist. The quintessential art model, wearing a frilly pink dress with floral accents, is taking over her own painting.

It must be boring having to pose, and stay still for hours on end. So the model decided to have some fun with the half-finished portrait of herself. She drew a face, not much different from a stick figure, to play with the artist who had attempted to capture her image.

Of course, in order to paint this cheeky piece, the model actually did have to hold this pose for hours. Not a single ribbon, or bow is out of place. Look how precariously her silk slipper peeks out from her petticoat, as delicate as a ballerina's. A smirk teases her lips, but her eyes really do look bored.

Many self-referential paintings will show the creator, making a picture within a picture. But this is a rare example of a painting, showing the model, instead of the artist, working at the easel. And it is also a playful example of the subject rebelling against the artist.

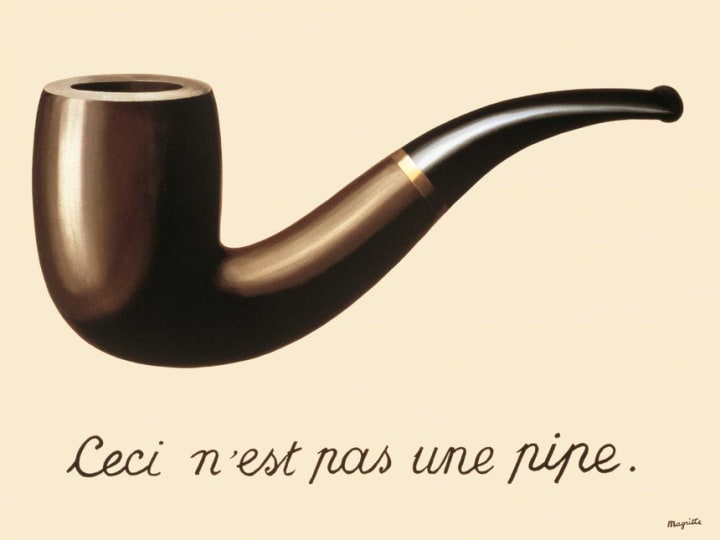

7. 'The Treachery Of Images'–Rene Margritte, 1926

This meta painting questions the link between images and words.

This painting is deceptively simple. Even it's title is complicated. It has been called The Treachery of Images, The Wind and the Song, or Ceci n'est pas une pipe (This Is Not a Pipe). This alternative title is also the caption on this painting of a tobacco pipe. This isn't a real pipe, it's a picture of a pipe.

This sort of meta-reference was a game changer for modern art, including abstract, absurdist, and surrealist schools of thought. Conceptual art continues to change with the times, for better, or for worse. This is one of the seminal pieces that inspired it all.

When we start to separate images from objects, and words from meaning, it's a slippery slope. For example, even though I wrote an article about Margritte's art, I haven't even seen the painting yet. I have never seen the physical canvas that he painted, at a museum, or anywhere else. I've only seen a depiction of it on my computer screen, technically speaking. Where does it stop? Is it just semantics, and splitting hairs? Or is it an important distinction? Art and reality are intertwined. Each inspires the other, perpetuating a seemingly endless cycle. And yet, there also seems to be a certain degree of separation.

French surrealist Rene Margritte was known for his mysterious, uncanny pieces. They are like puzzles that don't want to be pieced together, problems that don't want to be solved. This was a marked deviation from the established standards of art for his times.

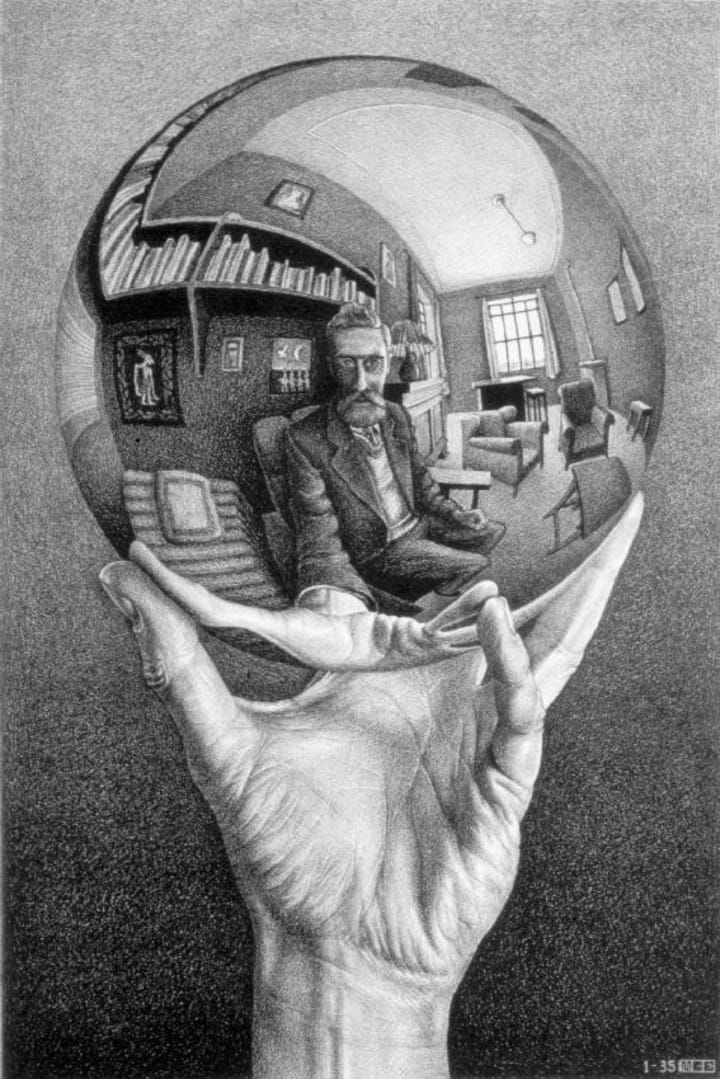

8. 'Hand With Reflecting Sphere'–M.C. Escher, 1935

The reflection of a mirror, plus the geometric properties of a sphere, makes for a unique self portrait by Dutch artist M. C. Escher

M. C. Escher is a famous Dutch lithographer, renowned for works such as the Metamorphoses, Relativity, and Waterfall. Escher was an expert at illustrating impossible objects, optical illusions, hyperbolic geometry, and tesselations. His creations were inspired by mathematical concepts, such symmetry, and even infinity.

With such an esoteric repertoire, this painting is a rare example of realism. Even so, the perfect mirror-ball is a highly symbolic object. The spherical surface reflects the artist himself. It distorts the individual fingers of his hand, delicately cradling the bauble. The artist is deep in self-reflection, literally and figuratively.

All of this texture and atmosphere is achieved in black and white. This greyscale picture captures so much emotion, in a subtle and understated way. I notice all of the books neatly arranged on a shelf. Escher must be scholar, or an intellectual. There are framed pictures on the walls. He must also be a man of the arts. Several chairs, and tables are strewn about, suggesting a large room. The large window has the curtains drawn, revealing an open world outside.

Conclusion

This was a brief timeline of paintings that broke the fourth wall by acknowledging their creators and audiences. There were many recurring themes in these varied pieces: Mirrors, self portraits, subjects that know that they are characters in an artwork. The meanings behind these paintings remain ambiguous. It is a challenge to interpret them, but solving the mystery is part of the excitement.

About the Creator

Cheryl Lynn

I am a blogger and freelance journalist, specializing in music reviews, band interviews, and other entertainment related articles. I have also published poetry, fiction, and creative writing. http://undeadgoathead.com/links/portfolio/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.