A Nerdy History Lesson: The Early Days of Anime in America

In our current day, anime is growing as one of the most widely loved forms of animation.

In our current day, anime is growing as one of the most widely loved forms of animation. There are so many different avenues and ways to watch anime and read manga. But it wasn't always like this for America; the anime industry had to jump through hurtles as high as mountains to get to the level of acceptance it is at today. To explain that, I'll explain first the difference between Japanese anime and American cartoons.

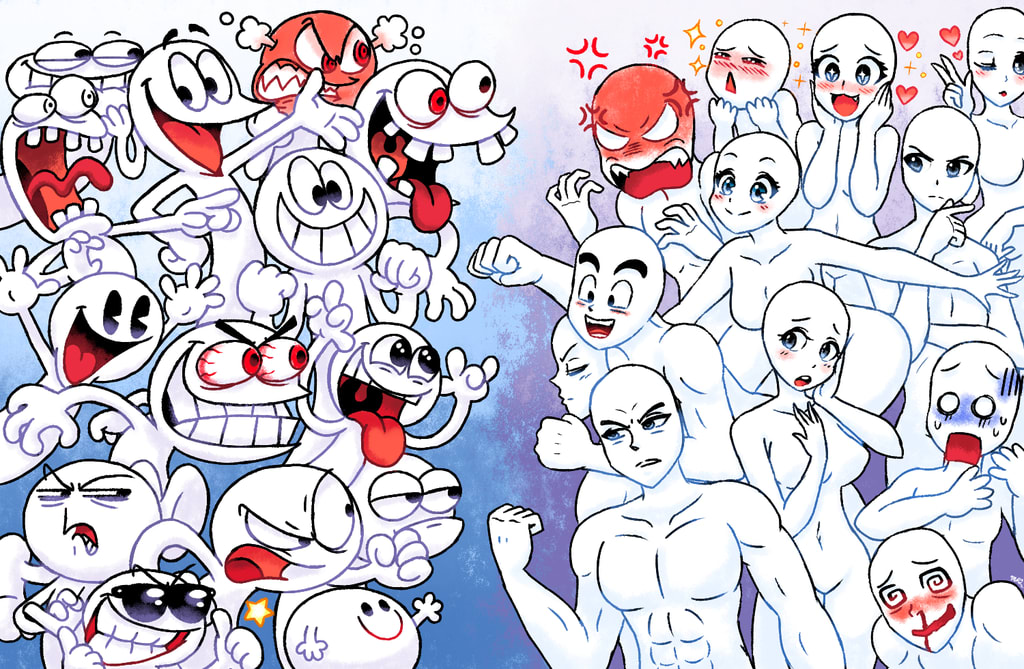

In Japan, the audience does cater to children, but its main audience target is younger to older adults. You can watch any anime series and see the emotional investment, its world-building traits, story-lines, character development, and drama. With that, anime has hundreds of different genres from action-adventure, romance, murder mystery, gore, space cowboys, school-life, and more. The colors, tones, and artistic style cater to the show and its storytelling. Some of it might be bright and loud, but often times has a simple, clean-cut drawing with soft, pastel colors. But the most important part to remember out of all this information is that for anime, the main protagonist will usually always be human in some respect. Keep that in mind for the next part.

American cartoons are known for having children as the predominant and only audience. Cartoons such as Catdog, Ren and Stimpy, Animaniacs, and Looney Tunes are the most well-known ones to have aired in the United States and are some you can remember yourself watching growing up. Cartoons have vibrant, loud colors with over exaggerated features because American cartoonist felt they needed these things to catch and keep children's attention. Another main feature is that the characters created for American cartoons were imaginative creatures, hardly human at all. And the reason for this was because of the introduction of anime into America for the first time.

In 1960 Astro Boy was the first anime to be introduced to America by a man named Fred Ladd, who was just a producer at the time. Ladd, however, is the one to be credited for the introduction of anime to the states altogether, and not just for Astro Boy. He was interested in the storytelling and the creative work that went into the production of Astro Boy and worked with NBC to host the show. Both Ladd and NBC had to jump numerous hurdles for the show to air, and still, the channel company only showed 106 of the 124 episodes it had planned to air. And even if the company managed to air all the episodes they had permission for, it would still be missing over seventy more episodes created. And on top of that, the ratings were in the toilet because at the time American people didn’t like the idea of “a cartoon character having human traits and feelings.” The show was taken down after a year from television; how crazy is that?

But as the years went by, more and more Americans started becoming interested in anime. After the failure Astro Boy brought, however, there were no television channels who would air anything. During the time, the only way you could access any sort of anime would be to be either (A) Japanese yourself with a subscription to Nippon Books, or (B) have a personal friend you knew who was Japanese, who had a subscription to Nippon Books. If you are an anime fan, and that name sounds familiar it should! Nippon Books is this nifty company that distributed anime in Japan and ordered directly from there. And within Japan they distribute most manga series; it's like the library of ALL anime. But if you had no access like that, you would have to live in an area like Los Angeles, California, that was home to small areas like Little Tokyo. Little Tokyo is a district in Los Angeles that emulated Japan by having many Japanese shops, restaurants, clothing, food and so much more. There, you could go into one of their liquor or bookstores to find authentic manga and anime that had been imported. The only real problem as an American anime fan was that none of it was translated into English—it would be just the raw Japanese. After some time though, Nippon began to print on the spines of the books and shows, a postcard to fill out, send back to Japan, and then weeks later send back a translation magazine you would have to read along with while watching or reading the show. And this whole process was the very beginnings of subtitled anime and manga—a salute to all the American anime fans who had to live through that process!

With all this happening, it still wasn't until the 90s when anime started making a more predominant presence in the public section. In New York, the first anime convention was held, just a small area where manga and anime shows were sold, still raw and untranslated. However, it was easier to get copies of shows and manga that people enjoyed and already came with the translation magazine instead of having to mail and wait for it yourself. It was because of this that subbing began in the anime culture. A “Subb” is known as having subtitles, meaning that it still had the original Japanese voice actors with English subtitles on the screen or completely edited in to read along without having to use the translation magazine. Because the 90s were also the rapid growth of computer and internet use, people began teaching themselves how to subb episodes and series of animes in universities and colleges. Some students would sometimes skip the translation magazine altogether and then put subtitles on themselves through research or by knowing the language. This became known as “FanSubs.” Students would create these fansubs and sell them to other people who were fans of anime yet didn’t know Japanese. Many online sites began to spring up, places to download or buy shows that had subtitles, which put a dent in the companies that had originally brought the shows over but were still raw. To stop fansubs, the American anime companies started a coalition called the Japanese Animation Legal Enforcement Division or JAILED. This company hired people to give tips to lawyers to hunt down these websites and the people creating the fansubs and stop them with legal force. In the end, it hindered and stopped a lot of the fansubs and also impacted the American anime company, since the people who bought the tapes for fansubs stopped buying them as well.

Disney, during this time, started noticing the fanbase for anime and decided to contract with Studio Ghibli for international dubbing and distribution. However, at the same time, Miramax ended up taking over Disney and taking more control of production within the company. Harvey Weinstein was the owner at the time, known in the television and production world as a man who would cut and butcher shows and movies regularly. Hayao Miyazaki, who was the owner and creator for Studio Ghibli was terrified that Weinstein would ruin the first movie in production Princess Mononoke. Miyazaki flew to New York to have a meeting with Weinstein, but before the meeting could begin, Weinstein received what is known now as the “No Cut Sword,” which was a small katana with a note attached warning Weinstein to not dare cut apart or ruin his movie. After some research, it came to light that it was Miyazaki’s producer who had sent the sword and not Miyazaki himself; however, he did add that, “Although I did go to New York to meet this man, this Harvey Weinstein, and I was bombarded with this aggressive attack, all these demands for cuts. I defeated him.”

Television companies, realizing that there was a fanbase for anime, tried again. Cartoon Network started a segment called "Toonami" which was a three-hour block during the later times of the day to host anime. When first introducing Toonami, they aired about five of their normal cartoons and two anime shows Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon. This was done as a test: Dragon Ball Z, being a show that catered to more male audience and Sailor Moon catering to the female audience, to see how the audience reacted and how the ratings would go. Both Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon smashed expectations and charted way higher than any of the other cartoons being hosted, and, by the next year, Toonami was hosting 19 new anime shows.

Coming into the 2000s, anime was making a bigger and bigger name for itself, and its fanbase was constantly growing. Television companies were now more excited about the ratings and popularity, which helped producers and artist to open and expand their ideas of what could be done with American cartoons. The first real breakthrough with American cartoons was a show called Avatar: The Last Airbender. The idea was pitched and hosted in 2003 by Nickelodeon. Although most of the drawings and art style were done by a company in South Korea, so it had a Japanese artistic style, the entire story-line, characters and idea came from Nickelodeon. The show was intended to target children from 6–11 years old, but after the first season, it became wildly popular with young adults ranging from 16 and up. The show continued on with three more seasons, a giant fanbase online, and became critically acclaimed and won numerous popularity competitions online.

So the trend continued. Cartoon Network began hosting a segment called Robot Chicken which was an air slot created for short story episodes that had much adult-themed humor. It had blood, cursing, humor, and was super popular with the adult fanbase. From there, numerous television companies began to expand and test the waters with more “adult-themed” shows. Family Guy, Archer, Bob’s Burgers, and Rick and Morty are just some of the shows that have sprung up during the years of animation. These shows began having more and more human characters, characters that adults could relate to, laugh at, or feel emotional for—a huge jump from the mindset in the 60s for Astro Boy. And even if these shows don’t have a set story-line like anime, they do have events and episodes that connect one another to each other, which keeps adults tied to the show and wanting more.

Japanese animation had a huge impact on the growth of American cartoons continuing into today's culture where merchandise is being sold in local stores, shows are being professionally aired and subtitled for everyone's enjoyment and sold to everyone in all age ranges. All I have left to say is just a nice big salute to all those nerdy anime fans who fought and brought us the good life we have today; cheers to you all and thank you!

About the Creator

Michelle Stone

Los Angeles, CA. Aspiring writer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.