Classic Movie Review: Lust for Life

The evolution from stage to film in acting, writing and directing captured in one movie.

Our classic this week on the Everyone is a Critic movie review podcast is Kirk Douglas and director Vincent Minnelli’s portrayal of the life of troubled artist Vincent Van Gogh, Lust for Life. If the film illustrates one thing more than anything else it is that acting has changed a great deal since 1956. While Douglas and co-star Anthony Quinn, as fellow painting legend Paul Gaugin rage at each other, it’s not hard to see why the directors of the next generation began to strive for something more natural and genuine from their actors. Lust for Life seems to me to be among the last films for which theatrically trained actors were the vanguard of the cinema.

Lust for Life picks up the life of Vincent Van Gogh as he is first rejected for a position as a priest. After pleading with a church leader that he must be allowed to minister and preach the word of God he is finally given an assignment. Van Gogh travels to a small mining town where he fails to connect with the mineworkers and their families with his scripted sermons. It isn’t until a parishioner takes Van Gogh into the mines that he begins to see that he must not hold himself above his flock.

The church is horrified by Van Gogh’s choice to live without the garish accoutrements his church salary should have allowed him. Their theory is that living a life of privilege away from the common people is to live as an example of what the poor should strive for. What they don’t understand and what Van Gogh completely understands is hopelessness, the way it seeps into the bones of people who’ve never known anything but toil and suffering.

While it is unspoken in the film, my interpretation was that Van Gogh was so moved by what he saw in the mines that he lost his faith in God and began searching for the meaning of life in his paint, a search that consumed him so deeply that his life ended at the age of 38 with suicide. Lust for Life hints that Van Gogh's suicide is part madness and part his belief that he was unable to capture the meaning and beauty of life on his canvas, even though today he is recognized as genius for capturing and enhancing the beauty of humanity and nature in his work.

When Van Gogh is dismissed from the church he begins dedicating himself to painting, specifically attempting to create art that respects a good hard day’s work. He wants to capture life on canvas but his restless mind robs him of the faculties necessary for managing the rest of his life. What little money Van Gogh received from his more successful and stable brother Theo, Van Gogh spends on more paint and canvases, even after he briefly marries a woman who has a small child.

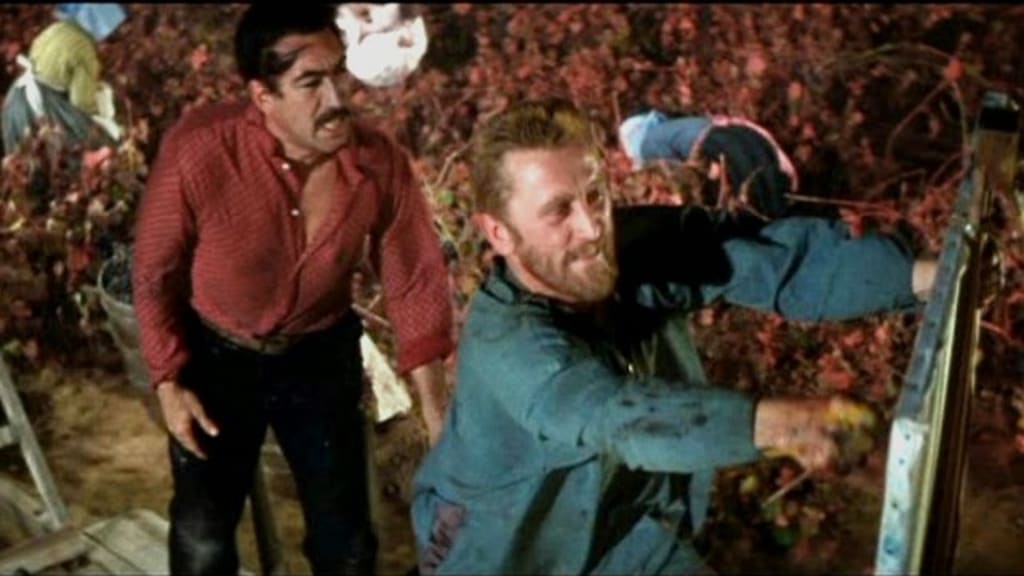

Lust for Life portrays Van Gogh’s legendary friendship with fellow painter Paul Gaugin as the most important and troublesome of his life. While Van Gogh learned a great deal from Gaugin their clashes over style and how to capture life on canvas drove each other to madness when they lived together in the late 1880’s in a small village south of Paris. Each challenged the other’s style with neither man gaining an advantage until finally they parted bitterly and Van Gogh, most famously, cut off his ear (Addendum, the story about Van Gogh's ear remains controversial with one theory, quite a good one, having Gaugin cut off Van Gogh's ear on accident in a fight).

Throughout Lust for Life, Kirk Douglas portrays Van Gogh with an almost ludicrous and off-putting intensity. This is magnified by the calm and reasoned voiceover in the film which is confusingly presented by Van Gogh’s brother Theo played by James Donald. I kept mixing up who was talking in these letters presented in the voice over, the perspective is Van Gogh’s but the voice appears to have been Donald reading the letters as if he were reading them aloud for our benefit.

Where Donald’s voice is calm and soothing, Douglas’s Van Gogh always sounds and appears as if something were trying to escape through his skin. That sounds like a terrible criticism of one of the most beloved and respected actors of his era but hear me out. In Hollywood in the 1950’s, the wheels were beginning to turn from a time when theatrically trained actors dominated Hollywood, toward those who’d begun to learn a more naturalistic style, one more closely suited to real life.

Douglas's pained and strained performance as Van Gogh as well as that of Quinn, are based around a school of acting where you're trained to take the stage where big gestures and vocal projection were as important as the dialogue and plotting. For years, actors were taught to try and reach the back row of a theater with their voice and make themselves larger via grand gestures so as to make sure everyone in the theater could hear them and understand the emotions they were projecting.

The Douglas and Quinn style of acting was then taken to the big screen by directors like Minnelli who had begun his career as a theatrical director. It was all that Minnelli knew before he first went behind the camera in the 1943 movie Cabin in the Sky. The same went for the writers, most of whom were plucked from Broadway and brought to Hollywood to write feature films filled with big emotional monologues and theatrical melodrama.

Having grown up myself in an era when directors are being schooled in realism, in grounding their work in some sort of realistic presentation of dialogue, and not having spent much time seeing stage plays, Douglas and Quinn’s ranting toward one another, the way Douglas contorts his face, Quinn’s hand gestures, feels stage bound to me and it keeps Lust for Life at an odd distance from my appreciation. I can’t relate to it, it’s so big and broad that it plays close to parody.

My education as a film critic came not from the masters of American cinema but from the French who embraced the form of cinema as an art form all its own, a way to present lives as they experienced them. The French from the very beginning used the form to capture life, while Hollywood throughout the earliest era of the talking picture, embraced Broadway and the theater and the tropes therein. That is why the musical held such an esteemed place in Hollywood until the 1960’s and then died off as filmmakers began to embrace realism as the ultimate form of the art of cinema.

Do I dislike the theatricality of Lust for Life? No, I don’t. While it’s uncomfortable and awkward to me there is also an elemental of truth to Douglas’s performance. Van Gogh is portrayed by Douglas with no judgement for his actions but with an aching sort of empathy and that comes from within him. Minnelli and Douglas long to understand what drove Van Gogh and in coming to understand him he becomes sympathetic. That is certainly a triumph for Douglas's performance, his style puts me off but his basic human decency and desperate need to communicate Van Gogh's pain makes the performance impactful.

I don’t view Lust for Life as a classic film but it does mark an epoch of cinema history. It’s a film, along with the musicals of the era like The King and I, for which Yul Brynner beat out Douglas for the Best Acting Academy Award, that demonstrates the slow, painful evolution of the American cinema from big broad and stage bound, toward the more naturalistic form we know today. Lust for Life is showy and spectacular in the way so many films of the time were; it fits the context of the times and only time and the evolution of the art of film have changed the way it is perceived.

Critics at the time of the film’s release were still trained by Broadway and the stage as well. Many of the New York Critics who were the most read and respected critics of the time in America, were also stage critics, and like the actors in the films they wrote about how they viewed the world from that 'belt it to the back of the room', melodramatic perspective. Things have changed over the years, and with technology, they will change again and Lust for Life in that way has a sort of historic relevance that time can’t strip away.

About the Creator

Sean Patrick

Hello, my name is Sean Patrick He/Him, and I am a film critic and podcast host for the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast I am a voting member of the Critics Choice Association, the group behind the annual Critics Choice Awards.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.