Kubo & the Importance of Stop Motion Animation

The charm and craftsmanship of the medium is worth a thousand Despicable Me's...

There’s a special place for people who still claim truth to the idea that animated films are solely for children, and whilst I’m not at liberty to damn said people to such a place, I can respectfully disagree and argue against the idea.

Yet whilst many are on board with the likes of Pixar and Studio Ghibli, the art of stop-motion animation is one that never seems to get the recognition it deserves. Case in point? Kubo & the Two Strings. The fourth feature film from Laika Studios, Kubo was released in August 2016 where it was met with critical acclaim yet failed to make a splash at the box-office, to the point where it struggled past its $60 million budget back worldwide. Sadly, this is common within this type of animation. Stop-Motion tends to be held in incredibly high-regard critically but is hardly ever a big hit with a wide audience (The Nightmare Before Christmas and Wallace & Gromit being exceptions). Yet whilst Laika’s films have never been huge commercial hits before they’ve never been too troublesome…until Kubo.

For those of you who aren’t aware, stop-motion is a laborious and beautiful form of animation that makes a physical object seem as if it’s moving on its own thanks to the use of photographed frames that, when placed together in quick succession provide the illusion of movement. Wallace & Gromit are Plasticine figures that appear to move, whilst Laika’s work tends to focus on 3D-Printed models that are painstakingly altered up to 24 times a second. It’s a process that allows you to actually see the effort onscreen, even the slight imperfections of a bad frame give the films a charm that CGI often can’t obtain. Every single vowel mouth movement is a separate slot for each character, changed from frame to frame. When a gust of wind makes our heroes’ hair blow, you feel the effort that’s gone into it. It’s not only in the craft that Kubo shines as a film, here is a family film that’s not afraid to shy away from the topics of death, mental illness and, depending on how you see it, domestic violence. It’s a timeless Japanese fairy tale (albeit, still americanised) that benefits from its style and is probably the best Laika film since Coraline. We’ve come a long way from the skeletons in Jason and the Argonauts…

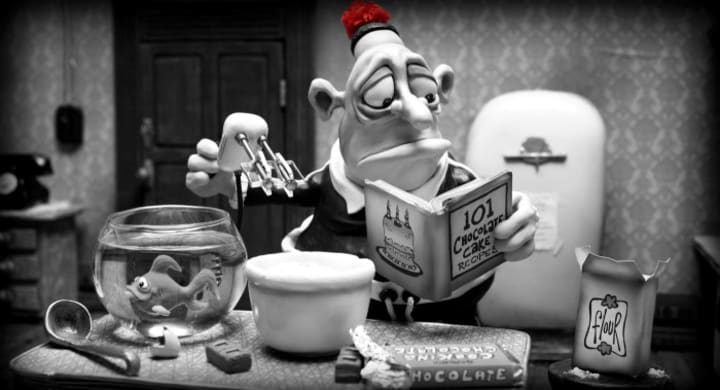

The largest ever stop-motion puppet (above) was used for Kubo.

The film even boasts world records for the largest stop-motion puppet within an intense battle between our heroes and a skeletal giant, but perhaps this is the issue these films have with finding an audience…is stop-motion too dark? Both literally and thematically a lot of stop-motion features include horrific imagery and sinister undertones, whether they’re the residents of Halloweentown or even the more adult themes seen last year in Charlie Kaufman’s adult comedy-drama Anomalisa (a great example of animation targeted at adults). This connection could be made to the movement the technique gives its objects, often stop-motion is noticeably detailed and imperfect, almost jagged; movement akin to that of monsters and ghouls who intend to scare the children out of their seats and have them running behind the sofa (or thrill them at the very least). It’s for reasons like this that it’s taken on a niche reputation among the public.

“Hey parents, why take the risk of scaring your child for a thrill when you can see this bright, fluffy CG happy film with contemporary pop songs that will shut them up for 90 minutes?”

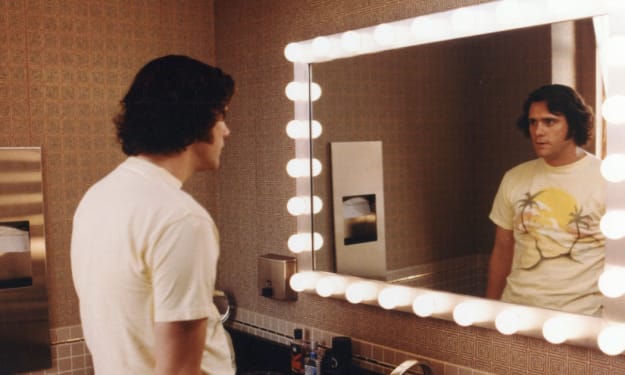

Mary & Max offers a deeply emotional and heartfelt look at mental illness in the form of animation.

I know that’s not a fair assumption to make but a lot of the time it’s frustrating to see so much talent go seemingly unnoticed by the majority. The exceptions are always going to be there, Chicken Run started Aardman’s hot streak with feature-length releases and Tim Burton’s name seems to slot into the presumptuous themes associated with the animation type enough to make the money back. But even Henry Selick, director of Tim Burton’s Nightmare Before Christmas (arguably the most culturally relevant stop-motion film) suffered massive box-office bombs with both James and the Giant Peach and Monkeybone (both worth checking out for artistry alone) before Laika gave him the reigns to Neil Gaiman’s Coraline, a film destined to find an audience thanks to the popular source material. Then again, the same could have been said for Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox adaptation, a film which once again garnered positive reviews but barely made its budget back despite being a Roald Dahl conversion (although years later Spielberg’s BFG would continue the trend).

Stop Motion is often utilised as part of larger productions to capture more realistic movement.

Of course, money isn’t everything, but with the trend continuing, fewer and fewer films are reaching out to the technique of stop-motion seemingly due to a fear of alienating a broad audience. It’s not like there’s no place for it, even on television the surreal and anarchic series Robot Chicken has won numerous Emmys and has continued for several seasons whilst piloting the formula. Various television shows such as Adventure Time and Community have adopted the technique for significant episodes, most of which are among the highest-rated. Despite being CGI, 2014’s The Lego Movie dropped its frame rate to create a stop-motion appearance whilst maintaining its bright and peppy attitude. Stop-Motion feels old school in many ways, its animation at its core though such care and detail is taken to create the world around the puppets and models that it’s no wonder the films usually withstand any financial trouble. You wouldn’t put that much effort into a story and script you wouldn’t 100% believe in. You wouldn’t spend hours moving the slightest piece of fabric three hundred times a day only to create a three second sequence. You wouldn’t inspire hundreds of children to attempt the exact same thing with Lego bricks and their webcams only to give up halfway through. You wouldn’t want to rob cinema of such a unique and creative medium, in an industry that claims to thrive on those very things.

I implore you, if you care for the medium to support it as best you can. Even with the financial trouble Kubo & the Two Strings still stands as the twelfth highest-grossing stop-motion film of all time. The big worry here is that after a period of time with similar results it may seem as though the interest is fading, and that couldn’t be further from the truth. Especially with Studio Ghibli potentially closing its doors forever, cinema needs studios like Laika and Aardman to continue to provide the antidote to the masses, to take as much pride in the craft of the characters and their movements as with the story. I know I personally look forward to every new piece of stop-motion I can see…now if you’ll excuse me, I need to go dig out my action figures, some wires, and a camera…

About the Creator

George Morris

[email protected] for business.

I write things and as a byproduct sometimes make things. Currently at University in Lincolnshire, UK.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.