Metropolis, Nosferatu, and German Expressionism

How these classic films relate to each other, and the German Expressionist film movement.

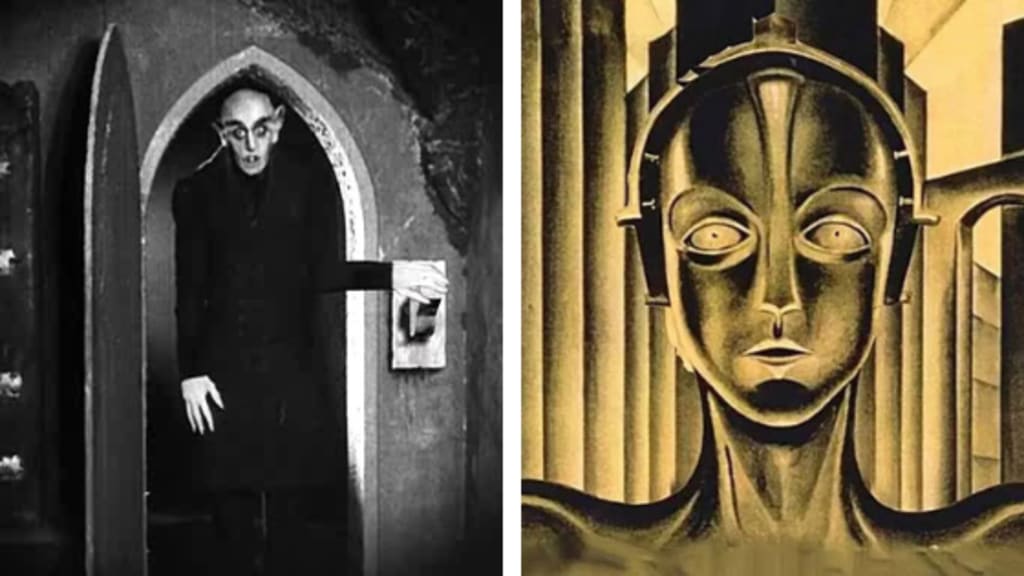

Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922) and Metropolis (Lang, 1927) are both very distinct films in several ways. One is set in the future, the other is set in the past. Both of these iconic expressionist films include similarities and differences in their themes and styles, and how they are used, which provide closure on the consistencies, and varieties of the German Expressionist film movement of the 1920s—and also their historical and cultural significance to Germany and World War One.

Nosferatu and Metropolis were produced during the German Expressionist film movement, and they share similar styles to each other, because of this link between them, resulting in their gothic imagery. However, they do feature unique qualities too, some inspired by other national cinemas.

The styles of performances of the characters in both of these films are similar to each other, and are very expressionistic. They are unnatural, as they are exaggerated performances, often used to express exaggerated emotions, or actions in expressionist films. Both films include this style of performance. For example, this exaggerated performance is seen in Nosferatu, when Ellen sees a vision of Count Orlok attacking Hutter for his blood while he sleeps, and hollers his name. It is also seen in Metropolis when even the image of the robot, influences the performance styles of the workers “in their dehumanised mechanical actions as soulless slaves” (Gunning, 2000, 55).

The appearances of characters also compare, as common expressionist trends can be seen in them, especially the villainous characters. Villainous characters are always presented with menacing features such as their stature, clothing, props, makeup, or their bodies themselves. They’re used to invoke fear, and it also allows audiences to identify villainous characters immediately. For example, in Nosferatu, Count Orlok has a tall intimidating stature with intentionally hideous facial features, such as his long nose, pointed ears, crooked fangs, and abnormally hairy eyebrows. He is also seen with black rings around his eyes, painted with face paint, he wears makeup, and is dressed in fully black clothing. He resembles a large bat with an oversized head (Silver and Ursini, 1997, 63). Metropolis is a great example to see differences in the characters’ appearance as the actress, Brigitte Helm, plays Maria (a protagonist), and the Machine Man (an antagonist). The appearances of these characters are not distinct as the Machine Man was to only capture her ‘likeness’, however, the Machine Man, while in the form of Maria, appeared with black rings around its eyes, while the real Maria did not. The dark rings around a character’s eyes appear to be a staple to expressionist character design, as they’re used commonly during the film movement, and by future films inspired by it.

Expressionist films used early visual effects to help create the worlds they made, because of how experimental the movement was. Murnau was incredibly creative with their use in Nosferatu, and Metropolis had the birth of new visual effects entirely; the Schuftan process.

Murnau used stop-motion to create supernatural effects, seen when Hutter is taken to the castle in the phantom coach by Count Orlok, and moves at demonic speeds (Eisner, 1965, 105). In the same scene, he uses negative film to invert colour, creating an unnatural, eerie, and demonic atmosphere (Silver and Ursini, 1997, 62-5). He also used superimposition to add an image over another, allowing for the fading effect seen when Count Orlok is killed by sunlight. In Metropolis, Lang also uses superimposition to include visual effects of electricity bolts, and rings to machines. This can be seen when the heart machine is destroyed as it appears to collapse and overload with energy. Metropolis gave birth to a new effect, the Schuftan process. It allowed for miniature models to appear large using reflections from mirrors placed between the models of Metropolis and the camera (Kracauer, 1947, 149). Actors would stand further away from the camera, appearing smaller, but the correct proportionate size compared to the large buildings the illusion made. This technique was used during the race near the Eternal Gardens in one of the first scenes of the film.

High contrast lighting is often utilized in Expressionist films, creating a contrast between black and white. It is often used for the effect of shadows, and is considered one of the key elements that make the expressionist style, and it adds to the mood. High contrast lighting is used in both films; however, Nosferatu appears to use it in more traditionally expressionist ways. Nosferatu uses it to create unease and fear through distorted images, seen in the films ‘staircase’ scene where a shadow of Count Orlok can be seen reaching for a door handle to get to Ellen. Metropolis uses the technique less extremely, traditionally, and uses it more to contribute to the mise-en-scene. An example of this is seen in the workers’ city. The city is lit by artificial light as it is underground, and shadows created by the skyscrapers are everywhere. They live in shadows, and they have no real sunlight in their lives. Here, the light is used as a symbol of their oppression and slave-like existence. Meanwhile, the upper-city of Metropolis shines brightly, and spreads luminous mist. It explodes with light (Eisner, 1965, 233). It is very clear that the people of Metropolis are free, unlike the workers.

The use of sets was extremely common in Expressionist films, they’re often used to create a claustrophobic effect, and further emphasize the ‘retreat into the mind’. Sets were heavily used throughout Metropolis. The film also used miniature models of buildings, and large areas to create the fictional city. It also used the Schuftan process to create the illusion that the miniature models were large structures. This can be seen in the ‘Moloch’ scene, where the machine overheats, and Freder has a vision that it is like a God demanding sacrifice. Moloch is a miniature model, which appears large using the Schuftan process in a set. Nosferatu is quite different as the film’s exterior shots are shot on location, despite being an Expressionist film; a creative choice by Murnau that is typically a Swedish technique that can be seen throughout the film. The jagged clouds, forests, hills, and mountains of the landscape keep the effect Expressionist sets create (Eisner, 1965, 99-100). For example, Wismar, a German city, was used for the exterior shots for the fictional city the film begins in, Wisborg. The exterior shots of Transylvania were shot in northern Slovakia, including Count Orlok’s castle, which is actually Orava Castle.

The style is extremely important to Expressionist films. Kael said that Nosferatu had “more spectral atmosphere, more ingenuity, and more imaginative ghoulishness than any of its successors,” and Ebert said, “It's eerie power only increases with age (Jackson, 2013, 8).” Similarly, Metropolis, and its mechanical sexuality, melodrama, and political critique are conveyed through its visual style and sets (Gunning, 2000, 53).

Metropolis and Nosferatu also share common themes between them that typically reoccur in Expressionist films, and have become staple themes of the movement, however, they do have their own themes which differentiate from it, and show certain individuality.

The themes of tyranny and chaos reoccur insistently throughout the movement (Kracauer, 1947, 77). The tyrant is the villain and an aspect which represents the ‘retreat into the mind’ during the movement, as do some of the elements of Expressionist style. In Nosferatu, the tyrant is Count Orlok. He drinks the blood of his unwilling victims, brings the plague to Wisborg through the rats in the earth he brings with him, and causes Ellen to sacrifice herself to stop his tyranny. In Metropolis, the tyrants are Joh Fredersen, Rotwang, and the Machine Man (who is created by Rotwang). Joh Fredersen wants to use Rotwang’s Machine Man to take the form of Maria, and encourage the workers to rebel against him and his oppressive treatment of the lower classes, so he can seem innocent. Meanwhile, Rotwang commands the Machine Man to “destroy Fredersen’s Metropolis,” causing chaos in the process. Both bring tyranny to Metropolis and the workers. Lang describes Rotwang to be the main source of evil in Metropolis (Gunning, 2000, 65).

The theme of love appears in often. Usually the traditional love between the man and the woman, the hero and their beloved. In Nosferatu, the love is between Hutter and Ellen, a couple who live together in the city of Wisborg. Their love can be observed on several occasions in the film such as when Ellen is upset that Hutter must go on a long trip, when Ellen has visions of Hutter being attacked by Count Orlok for his blood, and when Hutter is sat next to Ellen’s dead body, as he is grief-stricken by her deadly sacrifice. Elsaesser noted that Murnau was generally accepted as ‘German cinema’s most exquisite romantic poet’ (Jackson, 2013, 9). In Metropolis, love is formed in the story, and is more complex than in Nosferatu, because of parents, class difference, and power. Freder, the son of the mayor of Metropolis who is the oppressor of the workers, Joh Fredersen, falls in love with a working-class woman, Maria. Maria gives the workers hope, and wants change in their society, and becomes the face of the workers. Maria falls in love with Freder as she believes he is their ‘mediator’, someone who can help negotiations between the workers, upper-classes, and Joh Fredersen.

The theme of sacrifice is present in Expressionist films, a reflection of the sacrifice Germany gave during and after their humiliating defeat in World War One, which lurked in the mind of the nation so long after. Nosferatu features themes of sacrifice as Ellen, the “innocent maiden,” makes Count Orlok forget the “first crowing of the cock” by sacrificing her blood to him, and therefore herself. In doing so, Count Orlok forgets about the coming of sunrise by his temptation for blood, and dies when hit with rays of sunlight. His reign of terror and death is brought to an end with the sacrifice of Hutter’s beloved. Metropolis features themes of sacrifice differently. The workers, the lower class of Metropolis, sacrifice their lives in order to keep the city running with the machines they operate. They are more like slaves than workers (Kracauer, 1947, 149) as they are oppressed by Joh Fredersen, the Mayor of Metropolis, who believes the workers are “where they belong.” If the workers do not submit, their city would be flooded as the ‘heart machine’ would fail without their work. This is realized by Freder, who hallucinates the M-Machine is ‘Moloch’, a God who demands sacrifice from its slaves. In Nosferatu, a sacrifice must be made to end the tyranny. While in Metropolis, the workers' sacrifice is part of the tyranny.

The theme of death and loss also appear in Expressionist films. They go hand in hand as a reflection of the death and loss Germany suffered during World War One. They lost their men, land, financial stability, and national pride. Nosferatu features themes of death and loss more so than Metropolis. This can be observed when Count Orlok brings the plague to Wisborg from the rats in the earth he brings on his ship, causing many deaths. It can also be seen when Ellen dies when sacrificing herself to stop the tyranny of Count Orlok and Hutter loses his true love as a result. Out of all the death and loss in their story, nothing was gained. Metropolis, however, is different as there is less death, but arguably more loss. Furthermore, there is a gain for the victims of the story. Death can be seen when Rotwang dies when he falls to his death after a fight on the roof with Freder, when the Machine Man is burnt and destroyed by the workers; and when the workers’ children are presumed dead when they forget about them once their city had been flooded and lost, as a result of their rebellion. However, Maria saved the children before the city completely flooded and Freder became the mediator for the workers whom Maria said would come. He is the heart, which mediates between the head and the hand. It is assumed that Joh Fredersen and the workers negotiate, bringing an end to the workers’ oppression and slave-like existence; a much happier ending than in Nosferatu.

The theme of religion is present in Expressionist films. This may be because many people turned to the Church during the 1920s, and therefore the films had Christian influences in them. Religious ties appear in the form of the seven deadly sins as they have some part to play in both Metropolis and Nosferatu. In Nosferatu, the sin that occurs is greed. Hutter leaves for Transylvania to offer Count Orlok a property in Wisborg. In return, he is offered a large sum of money for his work. Hutter gladly leaves his wife to complete the work, and as a result, sets Count Orlok’s plan in motion, bringing the plague and death to Wisborg. Hutter loses the woman he loves. In Metropolis, the seven deadly sins are much more prominent. Freder goes to a cathedral in search of Maria. When he doesn’t find her, he visits statues representing Death, and the seven deadly sins. He asks Death to leave him and Maria alone, however, Death “descends upon the city” when the Machine Man, in the form of Maria, uses sin to bring chaos and tyranny to Metropolis. The Machine Man in the form of Maria fulfills a prophecy of the coming apocalypse in the Bible spoken by a monk:

“And I saw a woman sit upon a scarlet coloured beast, full of names of blasphemy, having seven heads and ten horns… And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet colour, having a golden cup in her hand… And upon her forehead was a name written, mystery, Babylon the Great, the mother of abominations of the earth.”

The theme of madness commonly appears in Expressionist films, as it reflects Germany’s retreat into the mind after their defeat in World War One. Madness presents itself in Nosferatu in Knock, a servant to Count Orlok. Knock sends Hutter on his quest to Transylvania, and is soon admitted to an insane asylum. He is obsessed with his master to the point of madness. Madness appears in Metropolis when Rotwang goes mad and carries Maria across rooftops, forcing Freder to follow him to rescue her (Eisner, 1965, 231).

Nosferatu features themes of the supernatural; another theme which appears in Expressionist works often. Count Orlok is the supernatural being in the film. He is a vampire, and shares the traits of one featured in Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula, the book Nosferatu is based on. The traits of Count Orlok include many things, such as his appearance, his obsession with blood, and his weaknesses (sunlight).

Metropolis explores themes of social class divide, a complex theme relevant to the film's story. The divide is between the workers, the lower class of Metropolis, and the rest of Metropolis, the people who live above ground. The workers being oppressed by Joh Fredersen—the film takes the divide to the extreme. The workers live a slave-like existence, sacrificing their lives to keep Metropolis running with nothing but wages, and poor working conditions in return. The workers lack all individualism as they move as one. They are forced to live underground in a uniform city, deeper than the machines they work to operate, in the workers’ city. If they do not obey and operate the machines, their city will likely be destroyed, and the city would flood, as seen in the film (Eisner, 1965, 225-6).

Metropolis features themes of the technological future, and the increasing reliance we have on it. Technology can be seen throughout the film, and it is obvious it keeps the city of Metropolis running with the manual work of the workers to operate them. When the workers' rebel, and machines are destroyed, specifically the heart machine, the workers’ city is flooded, as it was the only thing keeping it safe, showing the vulnerability that the over-reliance on technology brings. Furthermore, when the machines are destroyed by the workers, Metropolis eventually comes to a stop.

In conclusion, the German Expressionist film movement had common themes and styles throughout its existence, but it was not set in stone. Films “reflect the mentality” of the nation they’re produced in (Kracauer, 1947, 5-6). When Germany evolved as a nation through its struggles in the early 1920s, it is not surprising why we see variety in the film movement that represented their national attitude in the present day.

Bibliography

Eisner, L., The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, California: University of California Press, 1965.

Gunning, T., The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity, London: British Film Institute, 2000.

Jackson, K., Nosferatu [1922) – Eine Symphonie des Grauens, London: British Film Institute, 2013.

Kracauer, S., From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Silver, A. and Ursini, J., The Vampire Film: From Nosferatu to Interview with the Vampire, Third Edition, New York: Proscenium Publishers, 1997.

About the Creator

Nathan Allan

A student at the University of Sunderland studying film and media. I'm interested in a whole lot of things. I'd appreciate it if you stick around and read some of my articles on a variety of things!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.