Motherhood and the Other

Comparing Alien, Aliens, and Alien3

The association of family in the horror film is as old as the genre itself. Even as far back as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, themes of family are present (Cesaré is a creation of Caligari, so in essence, Cesaré is his son). American horror films followed this trend in Frankenstein (such as the conflict between the monster and Fritz, similar to sibling rivalry for the affections of the father, in this case, Henry), eventually recognizing the family in a literal sense with the sequels (Bride of Frankenstein, Son of Frankenstein). In his book, The Horror Film, Peter Hutchings discusses the concept of family horror and has this to say on the subject:

‘Family horror’ is a key term in much critical writing about 1970s US horror and usually signifies films in which the monster comes from within the family or comes in the form of a family or infiltrates itself into a family (182).

Hutchings is correct as many horror films from the late 60s and throughout the 70s and even into the 80s contained many themes of family. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), one such obvious example, as are The Omen (1976), The Exorcist (1973) and The Brood (1979). However, one of the most interesting additions to the subject of family horror is Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) and its first two sequels, Aliens (1986) and Alien3 (1992).

The idea of the family is particularly present in a distinct form in each of the three films, as is the theme of motherhood. Additionally, there is the theme of the Other. In his essay, “An Introduction to the American Horror Film,” Robin Wood discusses several different forms that the Other can take, including women, other cultures, deviations from ideological sexual norms and children.

These are the ones that come to the forefront of the Alien films and the theme of the Other comes heavily into play with not only the Xenomorphs themselves, but also with the series’ protagonist, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver). There is an inextricable link between Ripley and the Xenomorphs, and the Otherness of Ripley herself, in essence, makes her just as alien as the monster, a theme which is first introduced in Alien, expanded on in Aliens (complete with a showdown between the two alien mothers of the series—Ripley and the Xenomorph Queen) and finally culminating in Alien3 when Ripley and the Xenomorph become one and the same.

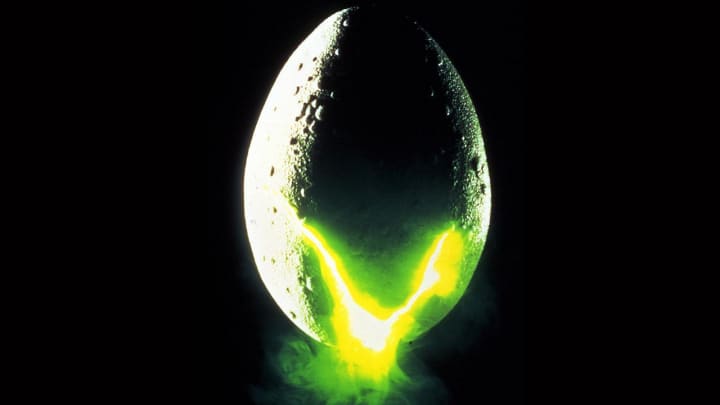

Alien

20th Century Fox

Although released less than a year after Halloween, Alien almost resembles a stalker film with some of the themes and situations, as laid out by Vera Dika in her essay, “The Stalker Film, 1978-81.” In regards to the representation of the killer, Dika has this to say: “he is either kept off-screen or masked for the greater part of the film. He is thus depersonalized in a literal sense, with his body and the more intricate workings of his consciousness hidden from the spectator” (88). Nowhere is this truer than in Alien.

In regards to other stalker films, there is usually some sort of reason for the killer’s rampage, but in Alien, there is no such reasoning and therefore, even more depersonalization than in a typical stalker film. This makes the Xenomorph itself distinctly Other from the crew of the Nostromo. Ripley also embodies this Otherness in herself, as the heroine typically is in the stalker film.

Although this lead character is most often represented as a woman, there is usually a certain ambiguity to her sexual identity. Since she is both like the killer in her ability to see and to use violence, and like the victims in her civilized normality and in her initial inability to see, she is portrayed with both male and female characteristics (Dika 90).

This relates Ripley to the Xenomorph just as much as it relates her to the other members of the Nostromo. There is a certain sexual ambiguity among all seven crewmembers as none of them are referred to by first names, only last names—Captain Dallas, Ash, Parker, Brett, Lambert, Kane. The two female members of the crew, Ripley and Lambert, are rarely seen in any sort of clothing that showcases their own femininity. As pointed out in Craig W. Anderson’s book, Science Fiction Films of the Seventies, there is a distinct separation between Ripley and Lambert:

Ripley is the more up-front person, while Lambert is reduced to sniveling and sobbing in the second half of the film, eventually perishing at the claws of the alien. The film has been praised, and rightly so, for having a heroine who is as strong as the traditional male hero, but little has been said about the stereotyped treatment of the other female crewmember (222).

This contrast between Ripley and Lambert is an important aspect in Ripley’s own characterization as an Other. Whereas all the characters in the film are sexually ambiguous in appearance and name, Ripley remains sexually ambiguous in action as well.

It is Ripley who sees the threat of the Alien before the other crewmembers and who protests when Kane, after being attacked by a Facehugger, is brought back onboard. Ripley remains the voice of reason and authority, citing quarantine procedure, a procedure which is ignored by all, including Captain Dallas and Ash, the science officer.

Although Ripley is third in the chain of command, her two superiors appear to lack the authority she possesses. Kane is silent throughout most of the film until he is attacked and left in a coma by the Facehugger and he himself gives birth to the Xenomorph when it bursts out of his chest. Dallas is ineffectual in his own attempts. His plan to locate the Xenomorph when it is still in its initial stages of development results in the death of Brett and his attempt to go into the air duct to find the Xenomorph and destroy it results in his own death. It is also Dallas who insists on bringing the infected Kane onboard the Nostromo, which seals the fate of not only himself, but also the entire crew.

The theme of family and particularly motherhood is in a light stage of development in Alien. The ship’s computer is named Mother and the birth of the Xenomorp is a perverse form of the Caesarian method of birth—instead of the doctor cutting the child out, the child bursts through the body of its “mother”—in this case, Kane. Ash makes a startling comment when the Xenomorph is loose on the ship, referring to it as “Kane’s son.”

Ripley’s Otherness continues to develop here, as she is almost seen as the true mother of the crew. The traditional authority figures all fail in the film—Dallas exposes the crew to the Xenomorph, Kane gives birth to it, and Ash and Mother seek to defend the Xenomorph for the purposes of the company’s weapons division.

So in the traditional form of Freud’s Electra complex, Ripley steps forward to overthrow the remaining authority figures (Ash and Mother) and take their place. We can see her qualities as a mother come forward in her treatment of Jones the cat, particularly at the film’s conclusion—she strips down to her underwear and lays in the cryopod with her arms wrapped around Jones, like a mother with her baby.

Aliens

20th Century Fox

Aliens was an interesting follow-up to Alien in that it is not a traditional sequel. The film avoided the name Alien 2 and instead chose with a plural version to suggest an escalation of the conflict between Ripley and the Xenomorph. In fact, the film has such a different style in comparison to Alien that one wonders if it can even be called a horror film.

In the book, Science Fiction Filmmaking in the 1980s, there is an interview with director James Cameron in regards to Aliens where Cameron has the following to say:

…that was our intention going in, to do a film that was not as scary … it’s scary, but it’s not as scary, but more intense, and I like to use the word exhilarating. Because I think you get exhilarated by the intensity of the kind of action that’s in this film (Goldberg 8-9).

Indeed, Aliens treads a fine line between horror and action, not unlike Cameron’s previous film, The Terminator. Aliens is definitely an action film and the use of action appears to overshadow the use of horror. In Alien, there was more of an effort to conceal the Alien, with it sneaking through air vents and nabbing unsuspecting victims, but that sense of fear seems to be diminished in Aliens.

However, despite this, many of the same themes of the Other and the family which were present in Alien are still present and even expanded upon in Aliens. In this sense, it can be considered a hybrid of horror and action.

The theme of the Other is still present and expanded on. As in a traditional stalker film, Ripley is not free and the monster plagues not only her dreams, but returns to physically threaten her once more. Aliens opens with the shuttle Ripley escaped in during the first film and she discovers she’s been in hypersleep for fifty years.

If one looks at the director’s cut of Aliens (Cameron’s preferred version), there is a scene when Ripley discovers that due to her time in hypersleep, her daughter grew old and died. Therefore, because of her encounter with the Xenomorph, Ripley lost her family—both the crew of the Nostromo and her literal family. With the concept of the Other, Ripley is still the only one able to see—no one at the Weyland-Yutani Corporation believes her story of the Xenomorph and it isn’t until they’ve lost contact with the colony on the planet where the Xenomorph was discovered in the previous film that they take her seriously.

In contrast to Alien, Ripley appears to gain a bit more femininity in Aliens. This seems due to her presence among Marines, where even the female soldiers take on masculine qualities. In our introduction to the prominent female Marine, Vasquez, she sports a boyish haircut and is doing pull-ups, with her muscles very obvious. One of her fellow Marines, Hudson, even asks her if she’s ever been mistaken for a man. Vasquez comments on Ripley’s femininity herself, jokingly referring to her as “Snow White.”

In this way, Ripley is distinctly Other from the rest of the Marines, a fact Hicks comments on when he says, “the new lieutenant is too good to eat with the rest of us grunts.” Ripley is separate from the rest of the Marines, serving as a consultant and not even venturing into combat with the Xenomorphs.

Ripley’s Otherness and identification with the Xenomorph is enhanced even more as a result of this, particularly with the introduction of the Xenomorph Queen in this film and Newt, a young girl who is the only survivor of the colony. Ripley takes Newt under her care, becoming a mother to the young child.

This creates an interesting link between Ripley and the Xenomorph Queen. Whereas in the first film, Ripley and the Xenomorph were only alike in their capacity as the Other, that connection is intensified. Now, not only are Ripley and the Xenomorph Queen Others, but they are both mothers as well.

This connection is made all the more personal because Ripley killed the Queen’s “child” in the first film and as a result of that encounter, Ripley’s daughter grew old and died without Ripley present. In a way, the Queen is responsible for taking Ripley’s family away from her, just as Ripley engineers the destruction of the Queen’s family.

This personal connection is brought to the forefront in the climax of the film when Ripley, armed with a “power loader” exoskeleton, engages the Queen in a form of hand-to-hand combat. Unlike previous encounters with the Xenomorphs, when guns or flamethrowers were used, this is a much more personal battle between the two mothers of the film, and the direct hand-to-hand combat signifies that.

There is an obvious connection between Ripley and Hicks, including a scene in the director’s cut when the two reveal their first names to each other. This is the only time that Ripley seems to be comfortable in being called by her first name as opposed to her more gender-neutral surname. Through Hicks and Newt, Ripley has found the traditional nuclear family of two parents and a child. In addition, it is this traditional family which has defeated the Xenomorphs, a much more unnatural family, at least in the eyes of society.

Because of this, Aliens could be seen as a reactionary film to Alien, a restoration of traditional family values. This surrogate family is fully realized when, once the Queen is shot out into space, Newt embraces Ripley and calls her “Mommy.” There is a return to traditional family values and it seems that the monster has been pushed back. It is a typical happy ending with Newt asking if she can dream and Ripley saying, “yes honey, I think we both can.”

Alien3

20th Century Fox

Alien3 is perhaps the most fascinating entry into the series. After the success of Aliens, a third film in the franchise was inevitable, but 20th Century Fox appeared gunshy towards the film. According to the documentary on the Alien3 special edition DVD, Fox went through many proposed versions of the film and several different directors were attached at different points until finally a young, first-time director named David Fincher was chosen (who would later go on to direct SE7EN). According to an article from the Senses of Cinema website:

Wrought with agony under the iron fist of Twentieth Century Fox, Fincher's vision for the sequel was demolished by the studio. Fox was plainly unwilling to gamble on an even darker version of an already depressing film, especially when handing over an unprecedented budget to a first-time director (Lindsay).

Fincher was reportedly so upset with the film that he disowned it and walked off production before editing even began. The result was an unfinished film that was a critical and commercial failure, with very small box office returns when compared to the film’s budget (Internet Movie Database). Despite these problems, an “assembly cut” version of the film was released on DVD, which shows a much more cohesive film than the theatrical release, and is much closer to Fincher’s vision for the movie.

Alien3 is perhaps the darkest and most depressing film in the series. Right from the beginning, the film alienated many fans of the series by killing off Hicks and Newt in the opening sequence. This decision, while controversial, is actually essential to Ripley’s further development and is perhaps the finest aspect of the film. Lindsay’s article on Fincher actually provides a traditional stock view of the film:

Alien3 replays much of the content of Ridley Scott's original Alien (1979). The outgunned and unprepared humans, unable to flee because they are adrift in space, overcome the odds and destroy the creature that is hunting them. However, the originality of Alien … is intentionally absent. Imagine a stock horror film where the defenseless teenagers simply surrender to the serial killer at the outset. They do eventually destroy the creature, but only because they have nothing better to do.

This view disregards some of the film’s most important aspect, particularly the downward spiral Ripley falls into. In Alien3, Ripley’s identification with the Xenomorph and as an Other herself comes to a powerful conclusion.

Just like the Xenomorph, Ripley has lost everything. The pair are lost on an unknown planet, their family eliminated and far from their home. In the previous two installments, Ripley had a connection with others. In Alien, she was a member of the crew, albeit something of an Other and the same goes for her time with the Marines in Aliens. But in Alien3, Ripley is viewed as something else entirely. The inmates of Fury-161 are religious fundamentalists who have taken a vow of celibacy and view the presence of a woman as a threat. Just as Robin Wood pointed out, this is a profound case of Otherness:

In a male-dominated culture … woman as the Other assumes particular significance … Woman’s autonomy and independence are denied (199).

This is precisely what happens to Ripley on Fury-161. Andrews, who is in charge of the installation, tells Clemens that Ripley must not leave the infirmary and if she does, she must have an escort at all times. It’s a classic case of patriarchal repression, truly brought to the forefront. Ripley is seen as just as much of a threat as the Xenomorph is, and in fact, she is regarded with the same disdain with several of the inmates calling for her death because they blame her for bringing the Xenomorph to them.

Ripley’s own Otherness is further defined in the film. Although she attempts to blend into their society by shaving her head, just as all the inmates are forced to, she still retains her femininity. In Aliens, there was a hint of a romantic link between Ripley and Hicks, but in Alien3, Ripley’s female sexuality, for the first time, truly emerges when she sleeps with Clemens. This completely alienates her from the rest of the inmates, who have all taken the vow of celibacy.

Even the Xenomorph itself has taken on a new form of Otherness, separating it even more from humanity. In the previous films, the Xenomorphs were born from human hosts. But in Alien3, it is born from an ox (dog in the theatrical release). This Xenomorph moves differently from the previous incarnations—it has a reddish color as opposed to the blue of the previous Xenomorphs and it moves more like an animal on all four legs while previous ones were bipedal.

Ripley has become so much of an Other that her and the Xenomorph become inseparable. She says to it at one point, “you’ve been in my life for so long that I don’t remember anything else.” It’s a profound moment for Ripley, when she realizes that her life has been defined by the Otherness of this creature and no matter what she does, she will never escape it.

But what becomes truly haunting is that just as in Aliens, Ripley has found a new family, but that family is the Xenomorph. She discovers she has a new Queen growing inside her and because of that, the Xenomorph no longer sees her as a threat. A particularly haunting line is when Ripley approaches the Alien and says, “I’m part of the family now.”

The theme of motherhood, which was very prominent in Aliens, has become perverted in Alien3, because Ripley is now the mother of the Xenomorph. On a planet where she is surrounded by religious fundamentalists, the view of Ripley as being the bringer of evil is enhanced because she discovers she is now the mother of the “anti-Christ.”

Ripley has become such an Other in this film that she realizes she herself must be destroyed. The idea of the killer and the final girl sharing similarities is taken to a new level in Alien3, because the final girl becomes the killer.

Therefore, Ripley plays a dual role in this—she knows she is the monster that must ultimately be destroyed. She has no hope of survival, nor does she have anything left to live for. She knows the Weyland-Yutani Corporation will simply extract the Alien from her and use it as a weapon. She rejects the chance to give up her “child” in such a fashion and in the perfect climax to the series, she leaps off the platform and falls into the molten lead, taking the Alien with her.

Conclusion

20th Century Fox

Three films by three different directors, each with a distinct style and vision. And yet, in each film, there is a cumulative development of Ripley’s character.

Each film can be viewed and judged on its own merits, but it is when all three are viewed in conjunction that their themes really work together to bring out the overall development of the relationship between Ripley and the Alien. A relationship which becomes far more personal over time than the relationship of any other protagonist and antagonist in horror.

Both Ripley and the Alien embark on a journey where they go from Other to Mother and finally to becoming one and the same, distinctly alien and the creation of something altogether different.

Sources

Alien3. Retrieved April 22, 2006, from Internet Movie Database web site: http://imdb.com/title/tt0103644/

Anderson, Craig W. (1985). Science Fiction Films of the Seventies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Dika, Vera. (1987). The Stalker Film, 1978-81. In G. Walker (Ed.), American Horrors: Essays on the American Horror Film (pp. 88-101). Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press

Goldberg, L., Lofficier, R., Lofficier, J., Rabkin, W. (1995). Science Fiction Filmmaking in the 1980s. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Hutchings, Peter. (2004). The Horror Film. Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited.

Lindsay, Sean. (2003). David Fincher. Retrieved April 11, 2006, from Senses of Cinema web site: http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/directors/03/fincher.html

Wood, Robin. (1985). An Introduction to the American Horror Film. In B. Nichols (Ed.), Movies and Methods vol II (pp. 195-220). Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

About the Creator

Percival Constantine

An action fiction novelist and a lifelong fan of comics and film. Discover my fiction at percivalconstantine.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.