Olivia De Havilland and the Breaking of the Studio System of Indentured Servitude

The Golden Age of Hollywood wasn't So Golden for the Actors.

Clarke Gable made a Golden Age of Hollywood career as a tough guy in a t-shirt. His carefully cultivated masculine aggressiveness on display to slap around everyone from Vivian Leigh to Joan Crawford, he reaped the rewards all the way down the boulevard. On the other hand, being typecast was a fact of life that even the biggest stars had to resign themselves to. "I have never been consulted as to what part I would like to play. I am not paid to think,” he once bitterly told Photoplay. On the other hand, did we really want to see “the King” weeping like Nick Nolte in Prince of Tides? Maybe but either way, this was the studio system, and it took two courageous actresses to actually hang a pair or two on the system of slavery that kept stars in both a professional and personal box during the studio era.

The precode institutional servitude emerged after the first million dollar Hollywood star succumbed to a front page scandal that captivated the nation. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle broke into film with Keystone in 1913 at a rate of $3 a day (or $72 in today’s world). His rotund features definitely played into his appeal and some believe his frequent co-star Mabel Normand was the first to wipe pie from her eye on the silver screen.

He went on to discover Bob Hope and Buster Keaton and played early mentor to Charlie Chaplin. In 1914, Paramount offered him $1,000 a day and 25% of all the profits on his films and artistic control.

The investment definitely paid dividends on both ends and resulted in a three-year $3 Million contract in 1918. But the high life all began to unravel because the silent screen legend chose an inopportune time to go to the bathroom.

On September 5, 1921, Arbuckle held a party in a luxury sweet in the St. Francis Hotel. On the way to relieving himself, he claimed that he found 30-year-old Virginia Rapp on the floor wreathing in pain, and his only intervention was to lift her back onto the bed.

The piercing screams were easily heard, but guests simply assumed she was drunk, and the situation was left at that by the time Arbuckle departed. Unfortunately, the pains did not subside, and the aspiring model died three days later of a ruptured bladder.

He said, she said: a Gross Injustice

Arbuckle’s fate was virtually sealed when her words eventually reached beyond the revelry. “He did this to me,” she claimed.

Pile Arbuckle’s 260 pounds onto the cause of death and the perfect storm swallowed up America’s biggest star. This, despite medical evidence, disproving any sexual assault. “The hefty star was portrayed as a fat brute who had pinned down his prey, rupturing her bladder, wrote BBC’s Jude Sheerin of the prosecution strategy.

The press was no better and enough jaundiced journalism swirled around the case that morality groups were calling for the death penalty. They also didn’t hesitate to use the fold to play up Hollywood decadence in general to further the storyline.

The flimsy evidence – led by a convicted extortionist and intimidated witnesses – resulted in two hung juries and finally exoneration. But the damage was done.

The legal bills would be unsurmountable, an unofficial blacklisting persisted, and the public simply believed the bad press. "Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle," the jury said in a written apology. "A grave injustice has been done."

Hollywood Scandal impacts Bottom Line

Hollywood didn’t have their star’s back either. "This was the first scandal in Hollywood with box office implications. Everyone had believed the stars were covered in fairy dust. Now that illusion was shattered, and studio bosses were terrified it would destroy Hollywood itself," film historian Cari Beauchamp told BBC

The Arbuckle case didn’t stand alone either. His sidekick Mabel Normand fought off three court cases, one involving the murder of lover -millionaire William Desmond Taylor in 1922.

Additionally, silent film actor Wallace Reid overdosed in January 1923, and the death of movie producer Thomas Ince on board William Randolph Hearst's yacht gave the establishment plenty of fodder to do a makeover on Hollywood's image.

Thus, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America was formed.

In parallel to the bad optics, a star fallen amounted to a significant loss. Going back to the silent era, studios put up large amounts of money to recruit, cultivate and market their actors.

Consolidation also Plays in the Hays Code

At the same time, consolidation would compound and focus the potential for loss. Originally, the division of labor was separate - production, distribution, and exhibition fell under different ownership.

The growth of the industry evolved to the point where each facet fell under a sole company. This was called vertical integration, and by 1929, five monopolies became responsible for 90% of the films. So a star gone awry, had an effect that went soup to nuts when previously the investment stratified through several companies.

This all helped usher in William Hays, who would later set up the Hays Production Code. Christian morality the backdrop, the general guidelines said, “No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin. Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented. Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation,” states the code.

So for example, the sanctity of marriage trumped the heat of the pre or post-marital. “In general, passion should so be treated that these scenes do not stimulate the lower and baser element,” the code dictates.

Forget any nudity and or anything vertical that leads to bedrooms of less than lofty origins. “Dances which emphasize indecent movements are to be regarded as obscene,” says the code.

Religion had preeminence and American liberty was not open for debate either. “The courts of the land should not be presented as unjust. This does not mean that a single court may not be presented as unjust, much less that a single court official must not be presented this way. But the court system of the country must not suffer as a result of this presentation,” the code continues.

Morality Clauses Aplenty

Thus the silver screen secured for the projection to the public, the Golden Age of Hollywood clamped down on the players. The seven-year contracts often included morality clauses. Stars were to refrain from drug use, alcoholism, divorce, and adultery. Women and men were to act like ladies and gentlemen.

In accordance, promotional work tied actors to social agendas set by the studios – thus allowing a great deal of control of the stars’ personal lives. Of course, if any difficulties could not be contained, morality was not applied to the authors – especially in consideration of freedom of the press. In other words, if violations occurred, studios infused the hush money or doled out exclusives to the papers in question.

Putting aside any official limits on workload or even complete payment throughout the contract due to declining marketability, freedom of expression also fell prey. Yes, if stars reached the heights, the payoff was high and work almost guaranteed, but artistic control was completely surrendered.

Typecasting is the Rule

The studio decided which roles had the most potential for profit and exposure. The typecasting alluded above was a frequent dispute, and as punishment for too much contention, the studios would lend them out to second-rate studios and lesser productions.

The actor’s only recourse was to refuse work. In such case, the salary was forfeited, and when returning, the studios would add the absent time back to the contract.

The first one to do something about it was Bette Davis. Unhappy with her repetitive roles and in search of better scripts and directors, Davis intended to uproot to England. Warner Brother’s responded with an injunction, and she took them to court in 1937. Davis lost, but probably speaking to her talent, better roles rather than a blacklist followed.

The Golden Age of Hollywood begins to Unravel

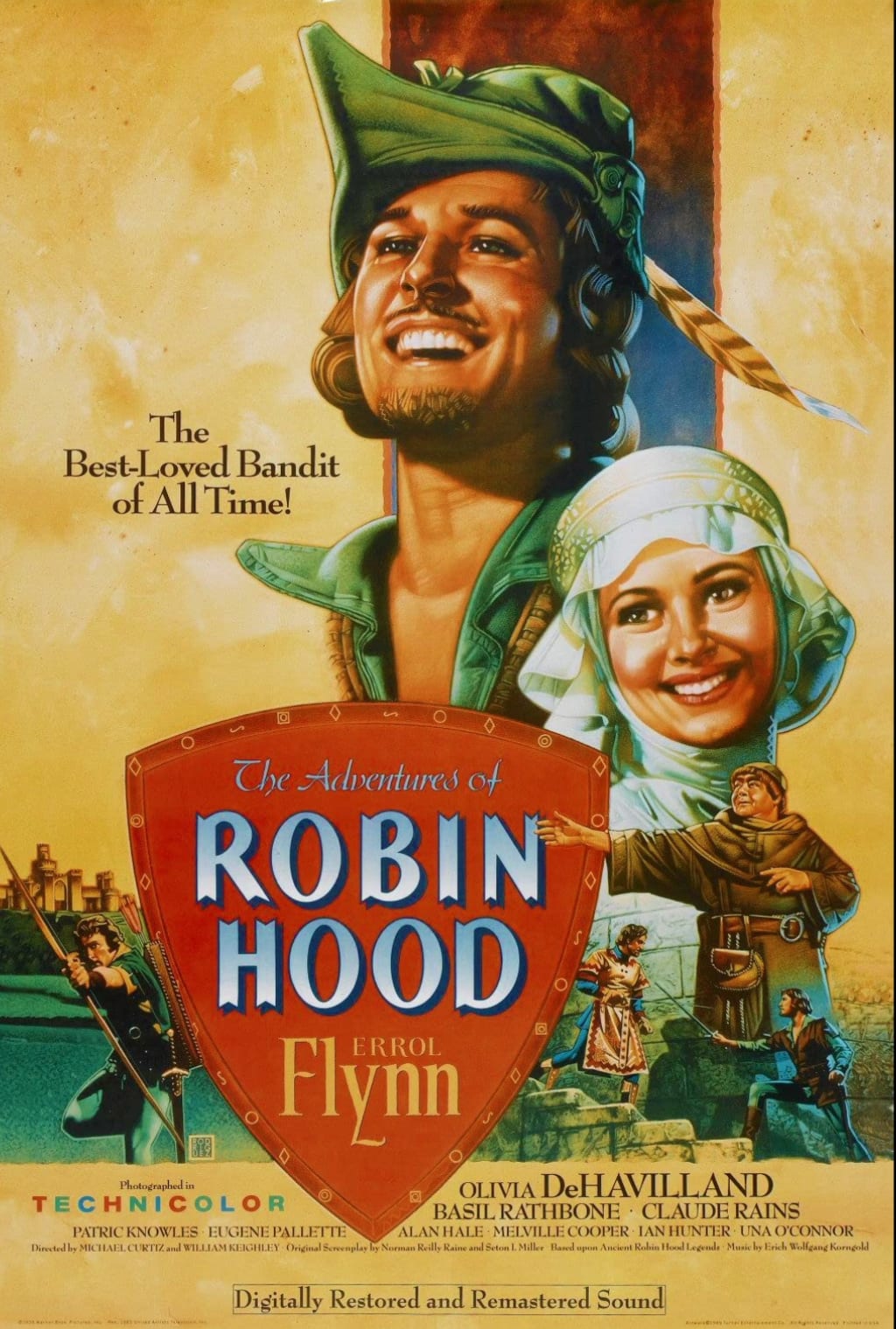

Of course, a precedent had been set – leaving Olivia De Havilland to take her stand. Also unhappy with the unchallenging roles, she told Sagaftra.com in 1994 that, “at Warner Brothers, a suspension was the immediate reply to an actor's disinclination to take on a particular assignment.

So she took them up on it in the early 1940s and went on voluntary suspension for six months without pay. Eventually, when her seven-year contract was up, the studio added the six months back to her original contract, and she was held in stasis.

As a result, De Havilland requested that the California Supreme Court release her from the contract. They complied in 1943, but Warner Brothers obtained injunctions and De Havilland was barred across the entire studio landscape. The litigation ensued for two more years before the court finally ruled in the pioneer’s favor on February 3, 1945.

The system had been broken, but the very real possibility of being blacklisted was still faced. Instead, the free market took over, and De Havilland’s talent had the studios lining up.

The moment is marked as the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age and maybe with good reason. It can be argued that executives carried an objectivity that enabled them to maximize talents of its stars – thus producing a superior product. Nonetheless, the price was too high. If you don’t agree, then try tying your talents to someone else’s directive and see how long you could tough it out.

Rich Monetti can be reached at [email protected]

About the Creator

Rich Monetti

I am, I write.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.