Why We Shouldn’t Complain (Too Much) About Changes in Comic Book Movies

Thought-provoking central conflict is one reason not to complain about the changes in comic book movies.

Captain America: Civil War (2016) is out, and comic book movie fans are rejoicing over its thought-provoking central conflict, great acting and thrilling action sequences (hello, airport battle).

But as ever, there are detractors.

This is okay in itself, since everyone is entitled to their opinions. However, some of the very pointed criticism centres around aspects of the adaptation process. These mainly revolve around the fact that Civil War doesn’t follow the comic book story line to the letter, and how the involvement of numerous characters has changed.

Indeed, the Registration Act of the comics (which forces heroes and villains to unmask and surrender to the government) is renamed as The Sokovia Accords in Civil War. Rather than focusing on unmasking hereoes, the Accords want to regulate and control our favourite heroes. Similarly, Black Panther is on a different side in the war, Spider-Man’s role is significantly reduced and various characters don’t event appear in the movie.

But why do people get so worked up about it? And, furthermore, should they?

Posing this sort of question certainly baits the ire of the more vocal fans, but before you pull out the pitchforks and torches, please continue reading!

By asking this question, I'm not being critical of the Civil War viewers in any way. As we all know, this sort of fan-agitation isn't limited to this movie, or just comic book movies, but to all sorts of adaptations, from Harry Potter to Shakespeare and beyond, as the meme below evidences:

It’s no good saying “it’s just a movie or television show” because we all love movies and television shows. Plus, this protection of, and passion for, characters and stories is truly commendable, and shows how important they have become to people and to pop-culture as a whole.

Fandoms, for all their quirks and eccentricities, are evidence of this emotional bond with the source material, where friendly debates and note-comparing are encouraged to perpetuate theories and affection for the franchise in question. And not to get too deep, but seriously, in this dark and cynical world, couldn't we all do with a bit more love and happiness?

However, with fans of comic book movies, it is a slightly different story. Due to the plethora or reboots and alternate worlds, playful competition and discussion between fans is par for the course, but in recent years it’s become a tad overzealous and problematic to say the least, with the divisions between Marvel and DC fans, abuse, racism and sexism becoming more pronounced online.

With so many films out, or due to be released, we have been truly spoiled with quality content. Not for nothing is this called the Golden Age of comic book movies! Nonetheless, in recent times fans have been taking to the forums to absolutely savage a movie for not categorically following the source material; but in doing so, are we forgetting some important things about the nature comic book adaptations- and the nature of film itself?

Should people hate the massive changes to a character or event in a comic book movie, just as much as its slight omissions and edits? Or is this just nitpicking?

The Mediums of Comic Books and Movies

The Dark Knight Returns & Batman V Superman

They can both feature eye popping visuals, and have though-provoking themes that are tempered by witty banter. Yet no matter how dynamic both can be, movies and comic books are fundamentally very different.

In comics, you simply absorb the pictures and the words and judge it on the success of these, as well as the pacing; in movies, there is a great spectrum of factors to take in, from the performances on show, the music we hear and the way each shot is crafted. Therefore, what constitutes as a good movie is different to what makes a comic book excel, because of how each is constructed.

This means that when a story is adapted to the screen, it has to be told a different way, compacting or emphasising elements of the comics. After all, on the page these stories have had weeks, months, even years to gestate, so it is very difficult to do the same thing in a two and a half hour movie.

So its to be expected that things are going to be missing.

Marvel's Daredevil makes good use of the TV format.

Arguably, our current golden age of television suits the episodic format of comics better. With the longer run-time of a full series, there is ample opportunity for expanding subplots and developing main threads. However, whilst it’s a big business, television doesn’t make as much money as a movie does.

Speaking of money, the way movies are consumed and packaged for general audiences also play a huge part in their makeup. Movies are marketed and hyped well in advance, with dramatic trailers, photos and interviews, to the point that we are bursting with desperation to see the movie.

As such, our expectations have been stoked to such high levels that it's hard for them to be met, which may go some way to explaining the bitterness that prevails.

Also, another reason why comics aren't straight up adaptations is because of their subject matter. With the propensity for violence, outlandish elements and themes (and in recent years, a greater amount of sex, foul language and drugs) in superhero comics, studios dumb these down problematic traits or omit them so that the film can cater more to younger audiences.

It’s no mistake that most superhero movies are PG-13. It’s purposeful, since a film has got a greater chance of making more money if it gets that age rating.

Remember Tony Stark's full-frontal alcoholic breakdown in Demon In The Bottle? As much as we'd love to see Robert Downey Jr sink his teeth into such a fitting and potentially award-winning performance, chances are that we won't be seeing a close adaptation anytime soon. After all, it's perhaps a lot to expect from the child-friendly Walt Disney Company in the summer blockbuster period... for now anyway...

They don’t make ‘em like they used to.

Daredevil and Mr Fantastic "wooing" their women.

Additionally, some of these popular comic book adventures take place well into their runs, and could only have occurred due to what had come before. Films cannot tell such long stories in the same way, and as such, traits have to change so that they fit into what has already been established in movie form.

This is especially apparent in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), since a straight up retelling - with characters such as Aleksander Lukin and long-time foe Baron Zemo - would be very difficult to accomplish without the movie feeling overstuffed. As such, they are removed so that the story hews closer to plot threads which had begun in The First Avenger (2011) and the wider Marvel Cinematic Universe.

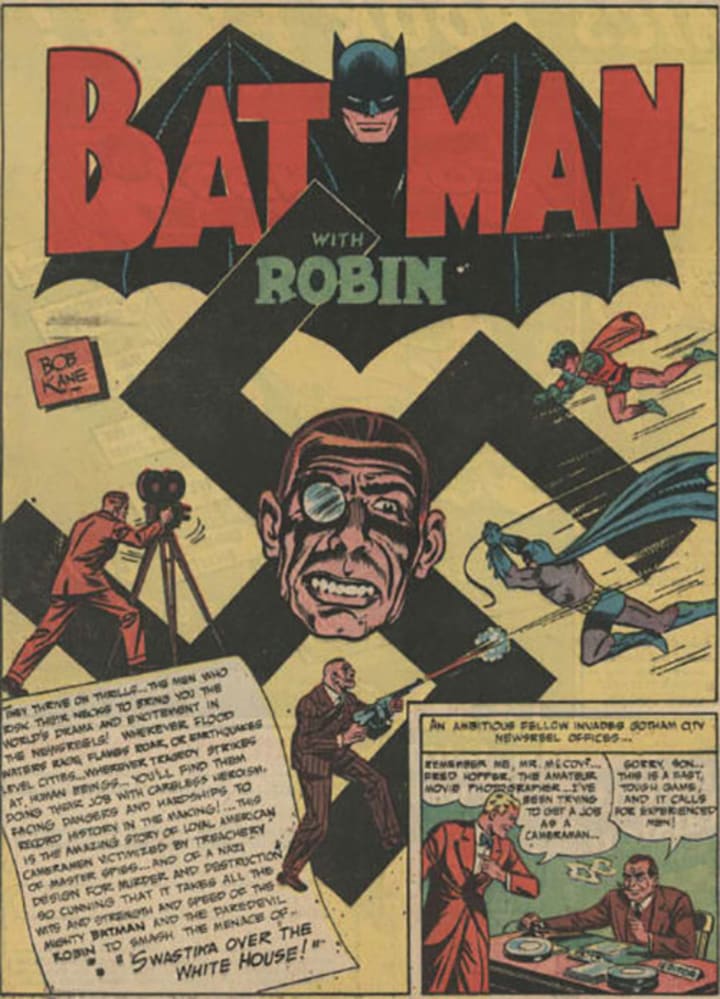

Another thing to bear in mind is that lots of these characters and stories were written many years ago. Indeed, Batman and Spider-Man have celebrated their anniversaries in recent years, which means that many of their iconic stories were written in times that are drastically different to the here and now.

In a wider historical context Batman first appeared the same year that World War II started, and Spider-Man appeared whilst Martin Luther King Jr. was campaigning.

In these times, things could be said and done that can’t be in today’s society, and therefore the films have to change to reflect the here and now. Hence why Marvel were so unwilling to portray The Mandarin as a traditionally racist stereotype in Iron Man Three (2013) and why, to increase racial diversity, Idris Elba was cast as the traditionally white character Heimdall in Thor (2011).

In cases such as this, change isn’t done to purposefully irritate comic book fans. It is done so that more people can go into the theatre to enjoy the adaptation and take pleasure in the stories and characters rather than feeling excluded or insulted. And, obviously, in doing so, studios can make more money.

"Wait till they get a load of me!"

There are always purists and conservative fans who believe that they know better because they’ve liked something for longer (we’ve all been a bit like that at some stage); so when something unexpected occurs, there is a viscous backlash, which is more often than not premature.

Because of the internet, this mainly occurs when casting news or trailers break onto the web, and comment sections are filled with opinions, where hatred breeds.

Remember the enormous furore over both Heath Ledger and Ben Affleck’s casting, with memes like this one below?

You’d be hard pressed to find someone who is critical of their efforts now.

The thing is, the clue is in the very word “adaptation,” which in many definitions discusses how something has to change or be modified or added to in order for it to work in its new form. Yes, we can argue that many things worked well previously, but that discounts what good has come from other variations of our beloved heroes.

Many people know and love the Batman villain Harley Quinn, but she is not a character that appeared in the main Batman comics. Moreover, she first appeared in the 90’s Batman Animated Series, which was an adaption of the comics by way of Tim Burton’s movies. Since then, she has been integrated into the main Batman canon, appearing in comics as well as other shows, games and even upcoming movies.

Harley Quinn in Batman: Arkham Knight (2015)

In a similar way, the symbiote that becomes the Spider-Man villain Venom became an aggression-heightening life form in the '90s animated series, and saw Peter’s personality become angrier and more arrogant when he wore it. However in the comics, its portrayal was far more benign. And we all know which version was used in Spider-Man 3 (2007)... (Though the less that’s said about it the better).

If the astronomically high standards held by some fans were adhered to when making adaptations, would Harley Quinn or the Venom symbiote be seen the same way, or even exist?

The bottom line is that without these fresh quirks, franchises would turn into rote, frame-for-frame copies that don’t offer anything that couldn’t be already consumed through by riffling through a comic book, and we would have none of the pleasures that fresh faces, new stories and different elements have to offer.

Conclusion

By no means is this piece suggesting that we can’t or shouldn't gripe about the things which we dislike in a movie adaptation; there’s no such thing as a thought police, and weighing up pros and cons are what fans do best.

However, do we really need overwhelming, polarizing diatribes over the smallest of alterations?

If the film has betrayed the essence of what made a character or story so appealing, then by all means it deserves some form of critique. Alternatively, does the good movie, which omits several smaller references, yet contains the majority of what makes the protagonist or tale work, really deserve the huge levels of hate?

Because, whether we like it or not, change is a default part of life, and adaptations will evolve as we do to cater to fresh audiences with new ideas and stories. Some good will come of them and some bad too!

And if all else fails, we still have our brilliant books to fall back on.

About the Creator

Max Farrow

A fanatical film-watcher, hill-walker, aspiring author, freelance writer and biscuit connoisseur.

These articles first appeared on Movie Pilot between Jan 2016 and Dec 2017. Follow me on Twitter @Farrow91

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.