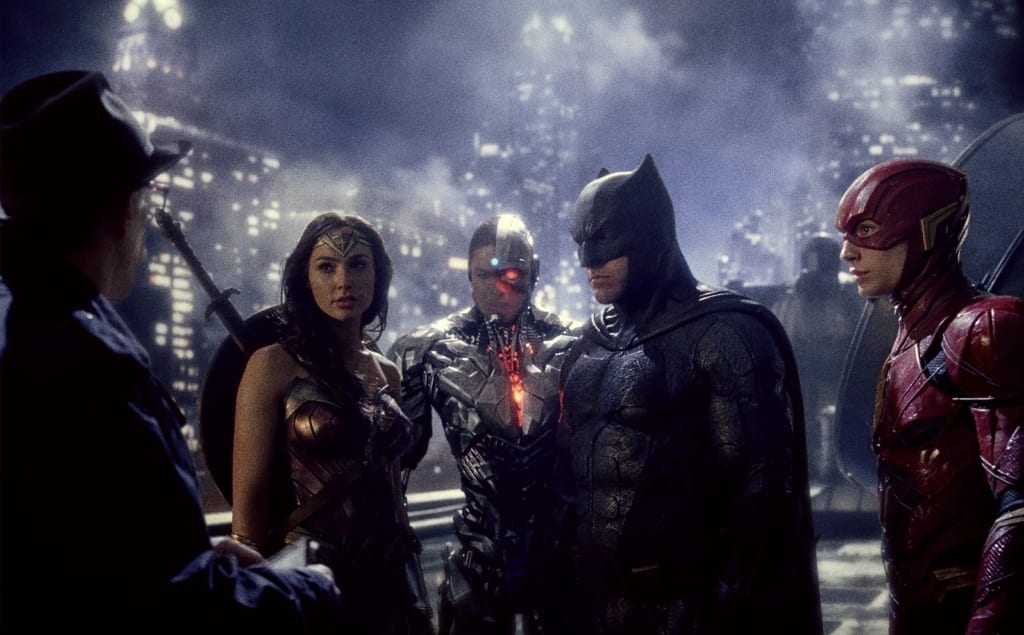

How Justice League’s Gravely Misguided Interpretation and Application of 'Show, Don’t Tell' in Dialogue Distances the Audience from Its Characters

AKA Zack Snyderisms 101

Justice League's release marked the christening of the namesake group of heroes on the big screen; the kind of cinematic event pure childhood wonder, larger-than-life fantasies, and whimsical role-play are made of. Usually. For a $300 million comic-book extravaganza—painted by many a skeptic as THE crucible of no return for WB's sprawling movie universe— whose primordial concern was supposed to be convincingly re-affirming its brand's struggling reputation to a new generation of audiences, this film sure takes viewers for granted. To better understand why, we must take a contextual look at what came before it.

Many aspects of DC's movie universe have been lambasted—the overpowering "gritty" aesthetic; the casting choices; the apparent urgency seemingly motivating numerous creative choices—but chief among them is Zack Snyder's predominant influence. At first glance, one could innocently surmise that Snyder was a shrewd pick for the down-to-earth, deconstructionist atmosphere that DC was going for. After all, he'd directed Watchmen, which did well enough critically at its release and has amassed a significant cult following in recent years. If he pulled off adapting one of the most complex and revered comic book stories ever printed, surely he was the right guy to go for in this scenario, right? The thing people often forget is that Watchmen was practically a panel-for-panel reproduction; meaning that most of what Snyder can truly be credited for providing to the project resides in the visual sphere. His proficiency here is unquestionable. It's his ability to do, well, pretty much anything else that is worrisome. He was given so much to work with on Watchmen that his strengths shined through. However, when faced with a much more burdening challenge, it became obvious that Snyder was way out of his depth.

Factions of diehard DC movie fans claim that he is gravely misunderstood and that Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was a film too mature for the general audience to appreciate. I believe the nuance to be found here is that BvS wasn't panned because it deconstructed its heroes, but rather because it did so in an extremely contrived manner. Oh, and to the detriment of... well, everything that is to be expected from a decent film. It didn't get any sort of preferential treatment for its "adult" ambitions; and rightfully so.

Dawn of Justice, after the novelty of seeing a freshly minted Batman—brought to life admirably by Ben Affleck, despite all of the movie's shortcomings—has worn off, is a tedious experience. It's filled to the brim with unnecessary literary references, unnatural, bombastic dialogue; artificial character beats and pseudo-philosophical dilemmas that are jarringly imposed on the viewer. As such, it becomes genuinely difficult to remember what's actually going down storywise at any given point. We jump from scene to scene at a frenzied pace, but hardly anything pertinent actually happens. Character development is a nonentity throughout; Bruce, Clark, and Lex all verbally state their emotional states and motivations, often nonsensically (in regards to the constraints of traditional narrative structure) or in vague, verbose sentences where too much is left to the imagination—Lex's fundraiser speech is particularly guilty of this offense. Screen time that should've been spent on growth is granted to grandiose montages that bear no utility to the plot whatsoever. Yes, Superman brings many of modern civilization's heretofore assumed universal truths into question. We get it. Henry Cavill has a derisory 43 lines in the ENTIRE film, most of them short and unnatural. His arc is one of brooding stares and absorption of others' dialogue. In all honesty, this take on the character has more in common with an emotionally insecure 14-year-old teenage girl than the illustrious figure of virtue we're accustomed to seeing in other media. A modernist, true to life portrayal definitely could've worked well had it been written resonantly; sadly, there's nothing of substance to be found here. This principle also applies to the movie as a whole: BvS either gives away too much or too little. Its successor fares no better in this regard.

Justice League, while tonally distinct, shares many of BvS's blunders. The characterization is flimsy; aside from their most evident quirks, the introduced heroes have next to no depth. They're blank canvasses of personality that the screenwriters haphazardly spray paint on to meet the plot's demands as the movie advances. The few distinguishable traits they do possess are expressed explicitly through shallow dialogue rather than narrative agency. This is most obvious in Aquaman and Flash's "recruitment" scenes. I will acknowledge the well-intentioned—but ultimately fruitless—attempt at depicting the intriguing father/son dynamic shared between Barry and Henry Allen. Unfortunately, the end remains the exact same; we're told by the latter about just how virtuous and hard-working Barry is in unmistakable terms. When delivered deftly, and with parsimony, in a crisp script, this CAN and often DOES work; take most of Christopher Nolan's filmography, for instance. If the ascertained characteristics truly reverberate with what is organically built throughout, it can serve a movie well. I believe "Show, don't tell" should be regarded not as an absolute, restrictive code but as a rule of thumb. Veering off-path a wee bit is fine. JL offhandedly swerves into a deep, deep gulch. There isn't the slightest peek into Barry's individuality following his introduction. No flashbacks or exploration of how his powers—a rich source of lore in the DC mythos—function. No secondary or tertiary plot devices that allow him to put his proficiency as a CSI to good use in the conflict, which could've have made for solid cohesion, building moments with the other members. After Bruce first introduces himself in his apartment, he retorts: "You said that like it explains why there's a total stranger sitting in the dark, in my second favorite chair..." The takeaway? He's a socially awkward nerd. An artificial one anyway. Remove it from the scene entirely and nothing is lost. Every single line in those painful few minutes is akin to this one. Does "I do competitive ice dancing" feel like something a living, breathing person, superpowers or not, would say when questioned insistently by a stranger who has broken into their home? Yeah, I thought so too. To top things off, he giddily accepts Bruce's offer without hesitation and gives no explanation other than: "I need friends." Those three cited lines perfectly encapsulate his flatness, which is only compounded by Ezra Miller's boisterous overacting—which would be more suited to a Will Ferrell movie—as well as his vaguely defined abilities.

On the other hand, Jason Momoa's turn as Aquaman is more realized; his abrasiveness naturally incites conflict, which is, well, paramount to any narrative. His presence within the group brings about friction, making for less yawn-inducing conversations between them. Yay, I guess. Regardless, holistically, he's yet another paper-thin rendition of a redundant cinema cliché. A self-pitying, apathetic loner who professes sayings such as: "Strong men are strongest alone" and instinctively resorts to physicality when piqued due to his occulted insecurities, he's exasperatingly dull. The charades get old as quickly as he goes on the defensive. Impressive, considering how this is his inaugural appearance on the big screen. Per contra to Flash, his immediate refusal of Bruce's proposition is laughably contrived. While their standpoints here offset each other, the scenes otherwise play out in identical fashion. "You should get out," angrily mumbles Arthur, before slamming his interlocutor against the wall. Bruce then proceeds to spew out what is no doubt one some of the most baffling expositional dialogue ever penciled: "Arthur Curry, protector of the oceans; also known as the Aquaman." As he seethes with rage, Batman looks him in the eye with the smuggest of faces—almost as if the screenwriters in charge were looking at the viewers by proxy, thinking "These idiots'll eat this shit up"—and proclaims: "I hear you can talk to fish." That's all she wrote. There's nothing else worth mentioning. Not a single facet of his identity is hinted at. Instead, it's shoved dismissively in our faces. I could go on for hours! But why would I take that kind of time when Warner Bros didn't even bother treating their most revered properties with adequate consideration?

Altogether, Justice League lazily skips over many essential tenets of good storytelling, effectively infantilizing its audience and sullying the original works it draws upon. It makes a farce of cinematic integrity in every sense of the word, albeit no one’s laughing here.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.